|

Clouds and Paddling Gail

Ferris |

|

There are clouds and there are clouds.† The next question for me as a kayak paddler

is what are they doing? |

|

01 |

|

As you can see in the picture above some wind is

blowing the fog over the iceberg just to the right of center.† I am viewing this from my kayak as I am

paddling out from the inlet. You can see by the size of the waves that the

wind is about ten knots.† It is a

bright summer day but that the clouds which are low and blowing from somewhere

to my left which is actually south to my right on the north.† This is not a storm coming in. |

|

Then again what about if I am in someone elseís

boat, a motor boat, what do I think about the clouds I can see. So there I was out with my friends on a Sunday

afternoon in their motorboat looking up at the clouds on top of the

rocks.† I wondered to myself is this

going to turn into a dicey deal while we are out here spending the afternoon

fishing, gathering mussels and picnicking. |

|

02 |

|

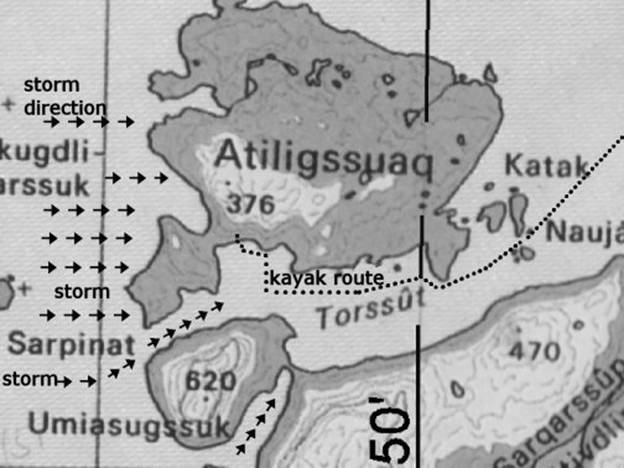

If I were out here in my own kayak what would I

be thinking? We were in the The dark brown stone walls were sheer rising 620

meters above the water. I was surprised I never knew this before in all

my years since 1992 of paddling in this area Upernavik the opening to Torssut

Passage behind |

|

03 |

|

So there I was gazing up at the clouds wondering

what is going to happen.† The clouds

were not moving they were just resting. We stopped the motor and dropped over the side

our fishing lines with baited hooks. † |

|

04 |

|

Drifting gently soon enough we caught some Ulk /

Sea Robins to roast and eat later.† We

upped our lines and were on our way through the passage Torssut away from

this threatening mountain, In past years when I have paddled through this

passage in my kayak there were several times when I had experienced wind

storms coming suddenly on me from the west across Baffin Bay with no warning. |

|

Below is a photo of Sandersonís Hope with some

orographic clouds to the west. |

|

05 |

|

On our way back the conditions as forecast were

as you see in the photo below quite benign. To the right is Sandersonís Hope

a pyramid shaped 3,800 foot high peak.†

Note that there are no clouds on the top of this

mountain which are called a hat. Local people look at Sandersonís because

clouds on top of this mountain indicated bad weather and that sort of

weather, usually very windy, can be really bad. |

|

06 |

|

Below is a photo of a ďhatĒ on Sandersonís in

1995 which I took because the forecast said Upernavik was to be hit by a very

violent storm.† Knowing that I happened to be staying at the home

of a friend in an area of Upernavik where I had a perfect view of Sandersonís,

of the coastline and most of the skyline I recorded the cloud structures of

this incoming storm as they developed. I wanted to document what clouds from a violent

storm coming into Upernavik look like because as a kayak paddler I wanted to

know for sure what I might be looking at rather than find out later when I

was the victim. The storm lasted for three days with 30 to 40

knot winds my friend laughed at me as I so foolishly had assembled my kayak

and set it on the rocks. As the violent waves and wind set in some friends

carried my kayak up to safer ground.†

The waves would have swept my kayak off the rocks or the wind would

have blown it off somewhere. † As much as I wanted to just launch my kayak and

go I did not have enough time to get away before this storm struck.† I was stormbound at a friendís house for

three days. Looking at this photo you would never guess

Sandersonís perfect pyramid peak is beneath this cloud cover. |

|

07 |

|

In 1992 in Upernavik when

I did not know what to look for when a storm is coming I started paddling

west in Torssut passage.† The day was a

lovely summer day but I noticed that there seemed to be this strange sort of calm.† The air seemed to feel stifling and It was

so calm that the water looked like it had been oiled. Just for curiosity I

paused paddling checked my wristwatch barometer to see if there was any

change.† No there was absolutely no

change since I had set out from Aappilattoq a few hours earlier. Then as I was nearing

the end of the passage a few miles westward I saw some puffy clouds filing

down a valley hugging the ground blowing toward me.† ďOh those puffy clouds are beautiful.† I have never seen anything like this

before.† Clouds here in the arctic are

so lovely and different than where I live in I had no idea what those

clouds in that defined array meant.† Sitting there in my

kayak I felt safe as in there is nothing to worry about.† I was still unaffected ††Wow was I naÔve. I looked at my

barometer again because I had been told that a change in barometric pressure

indicates a storm is coming.† I figured

that of course my barometer would tell me a storm is coming and that I should

just use my eyes to observe. And still there was no

barometric change.† Moments later I was

hit by fierce gusts that nearly snatched the paddle from my hands.† In alarm I knew now is

the time to tie my paddle to my bowline.†

Immediately I grab the long bowline I always carry at the ready on my

deck just in front of my cockpit and tied my paddle to it. †I knew just from practicality that resorting

to only fighting to hold onto my paddle was absurdly unwise.† Losing my paddle would have rendered me absolutely

helpless.†† |

|

Luckily there was some

time between the wind blasts because the wind was sporadic not continuous

like a katabatic or gravity fed wind which is continuous. I was able in those

pauses to assess where I was and where I could land.† I thought about reversing direction heading

for my old campsite. |

|

08 |

|

After first trying to

head back east and around the point I realized that the wind was so powerful

that it could pin me against those absolutely impossible to land anywhere on vertical

rock cliffs.† I could feel the

violent wind just shoving me over broadside to the cliffs. †I just knew how precariously unstable I

would be paddling down wind. I could feel it in my

body as I started paddling that the least risk would be for me to expend all

effort and head slightly broadside to the wind for the closest shore north

off to my right, where it was possible to land.† This shore only a few hundred yards away. I hunkered down and

put all my strength into getting over there, my only safe refuge.† Luckily there was a place to land and I

jumped out immediately dragging my kayak up on the waves. I opened the cockpit

sprayskirt pulled out as much cargo as possible to lighten the kayak.† Then I was able to heist it between my legs

and drag it to a limited extent.† At

all cost I wanted it out of harms way above the storm waves surges but of

great importance did not want to so as to not damage the frame or scratch the

hull up above what I estimated would be above the storm waves. I took my bow and

stern lines out and tied them off to big boulders, the bigger the better! When it is just you

and your kayak and you are all alone you realize that you must do everything

possible to not risk you kayak because you canít get there from here without

your kayak. |

|

09 |

|

I happened to have

been very lucky because I could have been paddling just outside the opening

of Torssut passage where there would have been no landing site for miles. At that time I really

do not know if I had the skill to paddle in such winds.† Later in The photo below is a close up of the clouds

blowing in.† This was my first

experience with such a storm.† The barometer did not register change until a hour after the storm had set in so I can tell you

without the slightest doubt that you have to watch the clouds not your

barometer when a storm of this type is coming in. This was one of those. The wind was blowing at something like 40 knots

and I estimate this speed because when I left my tent to get some water I had

trouble staying on my feet. I was very lucky to make land before it was

really impossible even paddling down wind to be in any control of my kayak. |

|

10 |

|

In the photo below is

what this storm looked like after I had set up my tent. You can see the wind

shadow on the water. |

|

11 |

|

My first shot at about 1 am below is a photograph

I took while peeking out from beneath my tent because did not dare open the

vertical zipper doorway my tent for fear my tent be torn to shreds by the

wind I couldnít believe what the sky looked like

looking straight up. Below are the clouds

driven overhead by the wind.† It sure

was windy! |

|

12 |

|

Note that the clouds are torn apart which is

probably the topographic effect on the cloud layer. Typically the temperature climbs for the first

four or six hours and then twelve hours later it drops to freezing.† The climb in temperature is due to

compression of the air the same principle for katabatic winds coming down

mountains. |

|

13 |

|

In 1995 another storm

in this same area just a mile or so east took place.† This time I had carefully chosen to camp

where everyone else stopped to camp and picnic.† Comparing notes and experiences I found out

why, from this experience.† This little

spot which is on the eastern third of the north shore in Torssut passage

happens to be sheltered as is indicated by the thick deposit of rich dirt and

lush plant growth there. |

|

14 |

|

The whole day was a bright summer day and I just

kept an occasional eye on the ridge across the way because I had never seen

this ridge covered with a shallow cloud all day like this before.† I thought it was curious. Then sure enough just

as I was looking at that ridge across the way to the south something started

happening to the cloud cover that had been clinging in the sense of slightly

draped over the ridge all day.† I could

barely believe my eyes as I watched both ends of the cloud starting to twirl

in opposite directions. |

|

15 |

|

This was something I never imagined I might

witness.† I was glad I was on land, not

in my kayak. I actually captured the development of this storm

on video and still camera because I happened to be standing just across the

way on the north side of Torssut with a good view to the south and west. |

†Below is a photo of the western portion of

this cloud.† Note that this cloud, just

to the center right, even though it is thin, is actually blowing down the

rocks. |

|

16 |

|

There I was watching as the end of the east end

started whirling and the same on the west end only they were whirling in

opposite directions Ė so much for the coriolis effect, I donít think that

applies to this situation. |

|

Well it certainly was

a down draft. †In fact my friend, John Kislov as well as plenty of others have

warned me to stay away from that side, the south side, of Torssut because this

area is notorious for downdrafts that will even flip motor boats right over. As you can see below

the cliffs are just straight up and down rocks 400 meters high. The photo below is

taken in 2008. |

|

18 |

|

With rapt attention I

watched across the way roughly a mile across.†

At first the water was plain navy blue but as I knew from previous

experience the downdraft would hit the water turning it silver. In the photo below I

also noticed that there was a build up of clouds behind where I could see in

the passage, Umiasugssup ilua, separating You can see that the

water is starting to show whitecaps and cats paws |

|

19 |

|

Then I began to notice

that low broken stratocumulus clouds were blowing up the passage from the

outside having come around the seaward side of Sanderson's Hope the highest

mountain at 1042 meters in this area.†

The front could not quite get past the outer mountain, Sanderson's

Hope mountain on Qaersorssuaq island but it must have been hitting Upernavik.

†† |

|

20 |

|

Gradually something changed because nothing

especially the weather can be taken for granted here except change.† The moving clouds the falling air off the

780 meter peak changed it's direction from west to

north and this began to do what katabatic winds do it hit the water at the

base of the mountain making whitecaps.††

I grabbed my cameras

because this was just the same type of event I had experienced in 1992.† I recorded the evolution of the wind first

hitting the water near the mountain then gradually the wind progressed across

the one mile fetch of Torssut hitting this area in an hour.† |

|

My barometric readings of this storm I observed

in 1995 which confirms the behavior of a barometer.† I estimate that there was about an hour lag

behind in the barometric measurements and the arrival of a fast moving

storm.† I learned from this experience that the barometer

does not foretell the arrival of this type of windstorm so I keep an eye on

the clouds.† I noted that the barometer had been hovering all

day at 1008 inches Hg.† My initial

reading at The time I think the

barometer reflects the windstorm situation more closely because when the

barometer has been holding for several hours during a storm.† Now when the barometer first starts to

rise, the wind will increase.† This

again is the lag effect and probably the section of atmosphere low pressure

area overhead has a steep or compressed gradient.† It is a relief to know

that when the barometer starts to rise again for the second time the wind

from the storm will start to slack off because the storm or low pressure

system leaving.† High pressure is

replacing the low pressure system. |

|

I took storm precautions by moving my kayak up

higher up the slope and tying it off to larger boulders. The photograph below of my tent was taken in 2008

even though it was not tied down for a storm you can what my tent is

like.† You can see it is a pyramid,

floorless with a tie loop on the top and along the bottom only.† I can reduce surface area exposure to the

wind by simply lowering the center pole.†

No other tent offers this option.†

Even though the tent is urethane coated nylon which collects condensate

I solved the condensation problem by making and suspending from the ceiling a

1.8mm ripstop nylon liner.† My exhaled

vapor passes through the liner condensing as liquid the tentís inner surface

or freezes to the outer surface of the liner. In Barrow To keep the tent warmer I had to add those snow

flaps which I ballast down with rocks or whatever is available to keep the

wind out. Baffin

Island Inuit say that the nice thing about a floorless tent is that ďwhen a

polar bear comes in, it is nice to go outĒ any way you can.† Luckily in |

|

21 |

|

To anchor my tent for heavy wind I devised a

structure of rocks to tie the tent down to the ground as low as possible.† I did this by tying a guy line from the

loop at the peak in the direction of the oncoming wind. To secure the guy-line from the peak I tied the

line around a small rock on the ground weighted down as low as possible by placing

a large boulder on the guy-line in front of the small rock so that the heavy

rock functioned both as a weight and as guide to keep the guy-line as low to

the ground as possible I also tied off all the bottom points with extra

lines from the corners and midsections of the bottom of the tent using this

same big rock in front of small rock. The sides were also staked into the ground with

large rocks on top of the stake lines.†

I was careful to arrange the rocks on the surface of the tent

fabric.† I added extra tent stakes use

more large rocks.† Then I decided to try

to reduce some of the slatting problem wind creates with this tent so this

time since I happened to have put in a second rescue rope 50 ft of 1/2 inch

line for difficult mooring situations I decided to guy the tent off.† What a difference so far, the tent is not

slatting as much as it usually does when the wind comes up.† The ropes go from a rock southwest to the

peak tie loop to a rock west, which is where all the wind will most likely be

coming from. So that is what I do

when I see nasty clouds upstairs. |

|

22 |

|

Gail Ferris gaileferris@hotmail.com 2 15 2009 |