|

My Arctic Experience at Pond

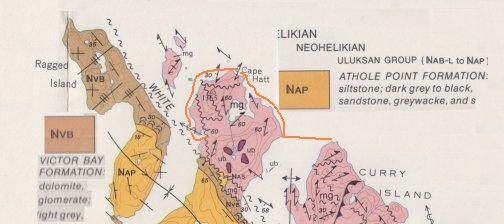

Inlet as a Sea Kayaker Gail E. Ferris www.nkhorizons.com/89PondInlet.htm |

|

The suspense of making

what seemed like an epic voyage started for me the moment I decided to make a

trip to the I had seen the boreal environment in |

|

plants that are forced by the wind to grow over rocks |

|

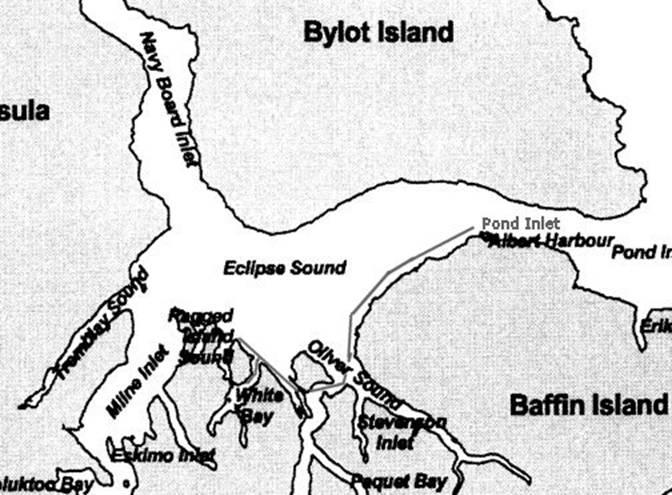

Upon scanning the NOAA Tides and Currents for Now the big question was, does the ice go out of Pond

Inlet, when and does the ice go out every year. |

|

|

|

From what I could find out I learned that the ice usually leaves

during the last week of July, if it is going to go out, and that the currents

are not severe because of the five to six foot tides. The reason for my concern about the currents

was that I did not want to combine paddling in freezing cold water with

threatening paddling conditions, such as tide rips and ice entrapment on my

first Arctic paddling experience. |

|

|

|

The weather, I learned

from some place, who knows? was moderate with light

winds averaging less that fifteen knots and temperatures warmer than other

places on The most precise source

of information for boating I found in the Pilot Guide at Mystic Seaport

library. My goal was to go

paddling in the I wrote for general

information to the Bureau of Economic Resources at Pond Inlet and wrote to

the Canadian government for information regarding ordering nautical charts

and topographic maps after having read that topographic maps provide better

information for choosing campsites than 1:250,000 scale nautical charts,

however from my on the water experience I found that the most likely

campsites are found at the mouth of rivers and streams, which are easily

found on either chart. I also made

note on my overall chart of the locations of traditional campsites designated

on a chart at the Office of Reneweable Resources in Pond Inlet to eliminate

some of the guess work. Then again you can have

this sort of situation that the map does not show in the photo below. |

|

|

|

Now the fun begins as the

hours of planning and gathering suitable equipment with all its paper work

and exchanges began. After hours of reading, deciding what to do about those

friendly little white furry creatures, the polar bear, who might drop by for

a snack on me. You know they don't

always remember to knock before opening your tent for you while you are

snoring away. In fact this on one of

those situations where being the incredible edible might become a

reality. Having previously learned how

to handle a shotgun I found I was in luck, because a twelve gauge doesn't

weigh as much as a thirty-o-six rifle, and once I became accustomed to a

pump, the pump shotgun is the fastest and least apt to foul during shooting

multiple rounds. Its

nice to know that I am desirable and to be wanted but I have my limits. With polar bears you aren't going to be

around to be able to say "I gave him everything!" |

|

|

|

My shooting friends found

that Mossberg in Thoughts of future

applications during duck hunting season also loomed in my mind. What a perfect combination a Klepper and a

twelve gauge when those little dinners fly by next fall. I'd like to see some one try that trick in

a Knordkapp. First they would have to

outfit the Knordkapp with auxiliary floatation to keep it upright the moment

the trigger is pulled. My friends had a few

amusing moments as I experimented with different styles of skeet shooting,

but gradually I became familiar and completely accustomed to handling my gun

so that I knew how to shoot it in an emergency condition. The next question was how

do you carry a shotgun on a kayak and have it both be dry and

accessible. The answer is to keep the

gun loaded on the deck in a dry bag which can easily be opened with one hand. The gun has to also be attached to the deck

and also the paddle because for some strange reason guns don't float and

paddles float away when dropped in the water.

I arranged a "Bone Dry" gun bag to be tied to "D"

rings sewn onto the deck. |

|

|

|

|

|

the shotgun is in the dark blue bag on the right, the sail

rig is on the left in the light blue bag, in front is the 50 foot throw rope

and down the middle is a 15 foot orange poly deck line coiled on the right

side. |

|

The nice thing about a

Klepper is that repairs can easily be done indoors because the skin and the

frame are easily dismantled and reduced to a size easy to bring indoors or to

ship on any airplane. The Expedition

Klepper skin can be repaired in below freezing temperatures with an ordinary

bicycle patch. Fiberglass boats can be

folded too but they just don't unfold very well. Below is the same model

Klepper I used in 1992 when I was in On the stern deck is my

solar panel that I used to recharge my video camera batteries. On the cockpit is the

video camera and on top of the map case is the GPS. |

|

this photo is of my newer red Klepper showing the solar panel behind

the seat, the video camera, the extra paddles, the Garmin GPS 50 and under it

is the chart bag |

|

Next question is will the

people at work let me take four weeks off in one block of time? Oh boy, what a thing to ask! Four weeks is a long time. I was so excited about

the trip that I was constantly consulting with anybody and everybody I knew

about any question that come to my mind such that my friends at work were

never hearing the end of my elaborate questions and ideas and by the time I

got around to asking if I could have four weeks off it was no surprise to

them and they were agreeable. Now I knew I had to go

through with my trip of a lifetime otherwise there would be a number of

people I would have let down; so I bought my airline tickets. That seemed simple enough. Then the plot

thickened as I discovered that shipping more than forty kilos of baggage

would not necessarily make it all the way with me to Pond Inlet and that

during early summer it was not unusual to have excess baggage delayed by two

weeks. With horror I imagined my

precious vacation time being wasted waiting for my baggage to arrive in Pond

Inlet while I stared helplessly at the water waiting for my Klepper to

arrive. Vainly trying to arrange for an air freight company to ship my gear

in advance to my destination in |

|

Arrangements were made to

air freight the gear to Now the next question was

how to take video pictures of my trip.

I had discovered on a previous trip that there is much better

continuity, and indeed the capture of motion accompanied by the record of

sound, which a video camera will record, projects a much more complete

communication with the audience that still pictures can ever provide. I knew that video cameras

had become small and light enough to consider using on a Klepper, but what

also had been introduced to the market was the Sony with a water resistant

case which was easy to operate and made very good quality video

recordings. I had found with other

Sony items that they are always ahead of their time. After hours of anguishing over the

financial commitment I purchased the eight millimeter Sony Cam-Corder CCD-SP7

and eight batteries. To my horror, I

learned that video cameras in cold conditions use twice as many batteries as

they do in warm conditions. I

desperately and vainly tried to find some means of recharging the batteries

either by solar panel or hand cranked generator, only to be treated as though

I had just landed from Mars during the Civil War era. Finally just two weeks

before leaving I spotted an advertisement for a store in After talking with my new

found friend, Gary Landau at Take-5-Audio in |

|

|

|

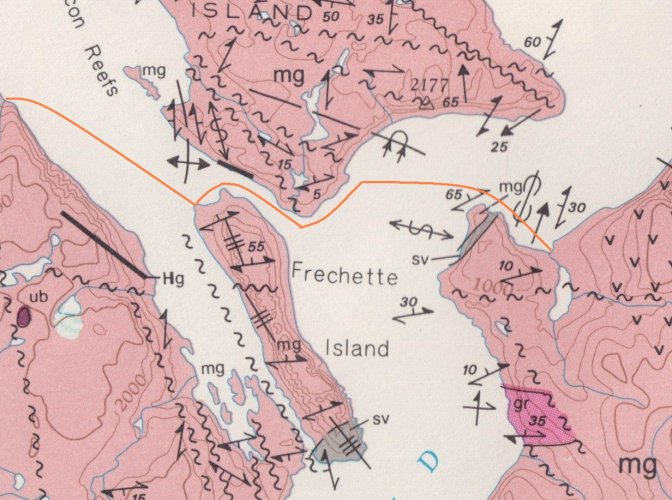

Navigation in this area

because it is so close to the magnetic North Pole has to be done without the

compass, because the compass will not provide reliable readings. The daily magnetic variation is twenty six

minutes, the deviation ranges between sixty five and seventy degrees west and

there are numerous iron ore deposits, one of which I saw and noticed that the

rocks have so much iron that they look like chunks of rusty iron scrap. With that I started to

realize that I would be confronted with two very confusing factors when it

came to navigation. Not only does the

compass spin around but the sun just keeps going around, never setting, is just

going along the horizon day after day.

Next what do I do on a cloudy day? After days of feeling

mentally like a helplessly confused navigator I raided my local library for

any books about solar navigation and purchased two books by David Burch

specifically written about emergency navigation and kayaks. I came upon an important

fact which I should have known long ago.

Did you realize that three hundred sixty degrees divided by

twenty-four hours equals fifteen degrees and therefore the earth rotates at

the rate of fifteen degrees every hour?

Thus each hour the sun has moved fifteen degrees in the sky. Well I felt better, but

next, you have to create a compass rose divided into fifteen degrees segments

starting at zero of three hundred sixty degrees for The solution I realized

had to be resolved by wearing a twenty four hour watch which also recorded

the date; otherwise I knew I was never going to know what part of the day it

was and what day it was. I might not

do very well getting back to Pond Inlet in time to fly home. I had visions of being

hopelessly lost with the sun going around and around and being completely

confused as to what day it might happen to be. Its okay to be dumb, but I

have my limitations and I didn't think that excuse would be very well

accepted at work as to why I returned several days late. That excuse would probably go over like a

lead balloon, especially since I am paid to perform scientific research, a

certain shadow of doubt as to my competence would be cast. The reaction of my co-workers would be

"Oh boy! Now we've heard everything!" The Bearing this in mind I

knew I had to seek a partner who had this character quality, otherwise many other

related problems could potentially develop especially since I am a very

fearful person. How about the polar

bears? |

|

The prospective partner

would have to had previous experience with cold water paddling and cold

weather camping. Minor mistakes in

judgment would unnecessarily complicate the straight-forward problem of

keeping warm and enjoying the trip.

Small items such as a hot cup of cider become a welcome reprieve from

the cold, but there is no compromise for the warmth of human intelligence and

understanding that is found among like companions and when that is lacking,

you might as well be better off alone.

A wrong decision based on ego and or ignorance can turn you into a

meal for the polar bears and ravens. Dealing with the Knowing as much as I do

about what effect the weather and topography as on paddling conditions, I was

unfamiliar with cloud formations, which indicated, wind direction and

barometric pressure and how make meaningful meteorological observations. I learned that when you

see lenticular clouds with a great combination of clouds; those lenticular

clouds are actually cumulus clouds being blown into that form by powerful

winds aloft accompanying a low pressure system. Do not go paddling unless you are in a

protected area and can easily put ashore.

Its nice to imagine that you can handle this, but it’s not nice to

find out you can't. Many fairly experienced

paddlers are unaware of the way cold water can suddenly drown even an

experienced paddler who is wearing a dry suit. Dry drowning where the throat closes up

upon immersion in this icy water is one unpredictable possibility. Another response is the

physiological reflex of gulping water into the lungs is initiated by sudden

immersion of the paddler's head in frigid water upon contact of frigid water

with the vagus nerve in the nose. The

paddler has a decrease in control of this response with aging. Cold water paddlers must wear

neoprene to reduce the shock of cold water to the head. I do not paddle in icy water as if I were

in the I got away with doing

some sailing for short periods when I was sure that conditions were suitable

I carefully avoided any erratic conditions and made sure that I could quickly

drop the sail and also just let it go if need be, because the sail was

designed to swing completely around the unstayed mast, if necessary. Sailing is a very cold

project here because all I am doing is just sitting there, whereas the

activity of paddling keeps me warmer. |

|

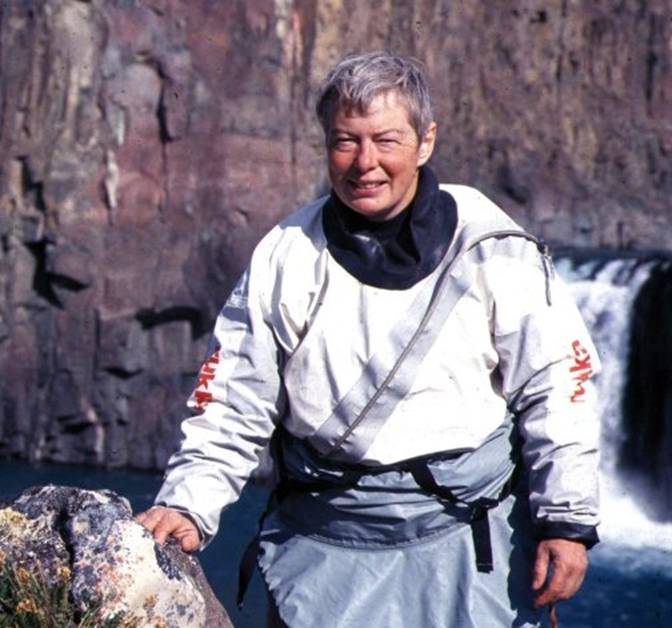

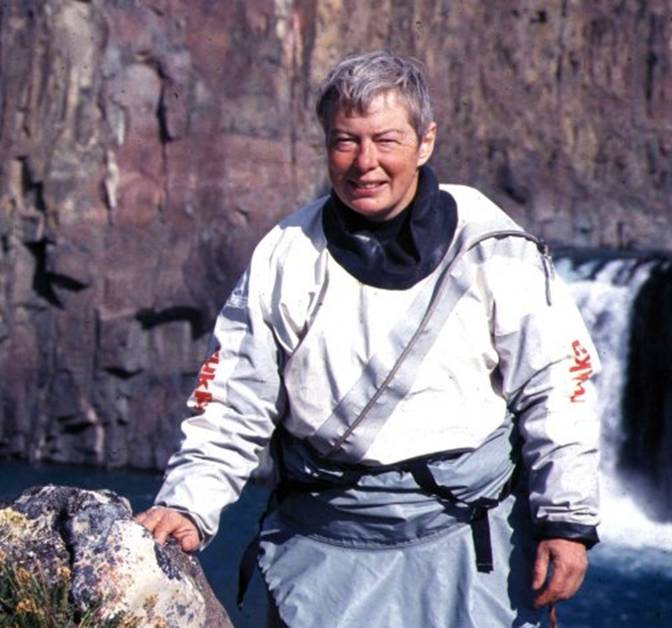

photo taken in |

|

I find it hard to believe

that there are still kayakers to refuse to wear either a wet suit or a dry

suit in Arctic waters. I always wear a

dry suit, which I have always found very comfortable and unobtrusive, durable

and tough during regular winter paddling.

During calm warm days the front entry diagonal zipper on the dry suit

is handy to open for ventilation.

Underneath two layers of light-weight polyethylene and a wool sweater

were comfortable. The reason for my choice

of the Aerius I Expedition Klepper was that it is easiest to fly to the Shipping ordinary

air-freight to the I learned the hard way

that it is often best to have the airline handle and store your

shipment. You should label your boxes

with your name, telephone number and date of your expected arrival with the

label "Hold for Arrival" on the boxes. Then check by telephone to find if all of

your shipment has arrived and it may be wise to have a separate waybill for

each box. When a box becomes lost it

is best to have had it only in care of the airline because they will recover

it for you not the local freight handler. |

|

|

|

There are misconceptions

about the Klepper, which relate to how well you prepare the boat for

paddling. If you notice that the boat

seems slow to paddle it is likely that you are paddling with soft air

sponsons and an unwaxed hull. I find

blisters on the hands are unsightly when pouring tea, so next time I'm

bringing my wax. The Aerius was not

designed for speed it was designed for touring at a reasonable rate. The best way to transport

the Klepper over ice is by sled, Would

you believe the Inuit invented this method just last week, just about the

same time they invented the harpoon? This

year, I only saw very rotten ice. My choice of tent was the

Gerry Mountain Tent, which is an above timberline, double entrance, semi free

standing design tent weighing about eight pounds. Next year I may use a Chouinard Mega-Mid

tent which has only a pole in the center, has no floor and is pyramid

shaped. The Inuit much prefer to camp

with a tent, which has no floor because "when the Polar Bear comes in,

it is nice to go out." I will

modify this tent by adding some pockets to hold ballast. The Mega-Mid tent weighs about two and one

half pounds, is easy to repair, is adaptable for other uses and most

important can be pitched almost instantly.

For camping on ice floes ice screws are used. |

|

|

|

Around the perimeter of

the tent and to protect your boat you will want to set up a trip wire with

explosive flares for those charming white hungry inquisitive visitors. I have not figured out the design of trip

wires, which are mentioned in Kingdom of the Ice Bear by Hugh Miles

and Mike Salisbury as being a very effective polar bear deterrent. On this trip I relied on the fact that being

with ten other people is a deterring factor known to apply to Alaskan Brown

Bears which I hoped would apply to Polar Bears and that we were in an area

less frequented by them and less accessible for them because the ice which

they on was out. Although it is not at all

wise to sleep out in the open without a tent because you look just like a

seal to a Polar Bear, you should have a bivouac with you in case of a

disaster to your tent. I brought a

non-rigid Gore-Tex bivouac, which was designed to allow you to have use of

your arms for cooking but also has a mosquito netting face guard. I had tested it many frosty nights at home

and found it excellent and easy to get in and out of. When it came to planning

on packing my kayak for bear country, which means just about everything, I

had the grand pleasure of finding out what it is like to reinvent the wheel

each time. Ignoring the sage advice of

my friends I used large bulky bags, which were most difficult to jam into the

pointed hull of the kayak. Watching

with horror and embarrassment as my friend unpacked his kayak in just moments

because he used long narrow nylon urethane coated bags. Packing my Klepper kayak was an awful

ordeal every morning because all had to go through the cockpit, there were no

loading ports. The large PVC coated bag

which I had allocated for my sleeping bag had the insidious habit of drawing

air in through the seal thus re-expanding it to an unloadable size if I

delayed in loading it immediately after filling and expelling excess air from

it. The PVC binds on any other surface

as well as becoming too stiff to form a seal in 40 degree temperature range. On my deck I kept my

shotgun in a "Bone Dry" bag made by Adventures and Delights in |

|

For a padded seat I sat

on a partially inflated Voyageur's Caboose bag with my clothes in it, which

made an excellent seat of variable height and softness, depending on how I

loaded it. It not only saved carrying

a seat but increased the loading volume and the paddlers comfort and gave a

measure of control over the position of my kayak's center of gravity. I purchased the Klepper S-1

drift sail in early spring and learned how to sail my kayak empty without

leeboards very conservatively in the cold water for two reasons. The first reason was to satisfy my

curiosity on what it is like to sail a kayak and the second was to have as

alternative means of propelling the kayak other than paddling for safety and

as a diversion from the monotony of paddling.

Dieter Stiller at Klepper

in The hull of the Klepper

has an unusually large margin of secondary stability because of the above waterline

surface area created by the sponsons, which the boat can actually be heeled

over onto this surface when sailing on a broadside reach. Essentially you have two types of hull in

the Klepper hull. I found sailing the

Klepper after so many years of paddling to be an absolutely delightful

thrilling experience. Cruising across

the harbor without lifting a finger, without making more than just the

slightest sound, being that of the hull passing over the water leaving a

delicate wake just seemed so extraordinary; and yet the entire boat can be

broken down to fit into canvas bags. Now if you are

resourceful the most secure method to ship your Klepper to the With a little stuffing

here and there and the judicious use of a broad brimmed hat you cannot only

ship your Klepper right beside you in the adjacent seat; but you can ship

some underwear, socks, clothes and sunglasses all as components of your

"Klepper" friend. Not only

that, but you can order double drinks and nobody will know until you try to

negotiate standing up sometime later, that the drinks you ordered for your highly

reticent companion just happened to have been consumed by yourself. Now of course either you want to do a

strenuous amount of weight lifting before trying to board an airplane with

your "Klepper" companion so that you don't create the appearance of

struggling with your shy friend or, heaven forbid, performing any unnatural

acts when boarding the airplane. I would suggest that your

"Klepper" friend board in a wheelchair and that solution avoids

these little problems. Now how

feasible would it be to fly with a fiberglass kayak as a passenger next to

you. Somehow I think it is not likely,

even if you were to saw your fiberglass kayak into sections, you would

probably be arrested and charged with traveling with an alien. |

|

Northern Fulmars on the water off Pond Inlet |

|

For food I brought an assortment

similar in character to my regular diet, because keeping a routine lessens

the stress of travel. I made it a

priority to bring some items, which I knew I especially liked and could add

to embellish a less interesting meal.

These were nuts, spices and butter.

The butter was unusually pleasing when I found mushrooms to

sauté. I feasted on mushrooms with my

friends from Food has to nutritionally

balanced in each of the three meals because the

physical demands of paddling all day and emotional demands of travel soon

become compromised and the trip becomes an ordeal. Freeze-dried and dried food works well as a

base to which you can add to. I found that individually

packaged freeze-dried food was bulkier than necessary and I plan to work out

a different system next year.

"Knorr" dried cup soups were always pleasing for lunch,

which I made during breakfast and stored in my "Nissan" stainless

steel thermos. I dried at home in the

oven at less that 200 degrees F. a couple of corned beef briskets and If you can get some seal

of char from the Inuit, by all means try it, they are both very

delicious. If you suspect your diet

may be deficient in enzymes and vitamins eat the seal meat raw. |

|

After all this

preparation it seems as though I'm never going to get on the water. After hanging around town waiting to

recover my last box, which had become waylaid in Iqaluit. I put my Klepper together and found that

nothing had broken during shipping.

Next time I will ship from |

|

Above are the couple who guided this trip

they were from Paris, Ancien Homme. |

|

Due to unforeseen

circumstances I teamed up with this group of ten people from We left Pond Inlet the

next morning in overcast conditions with a wind from the east at about ten

knots heading west with out ultimate objective as Milne Inlet. Bert Dean, the Reneweable Resources officer

showed us on the chart where the traditional campsites were, advised us of

potentially dangerous crossings, how to handle them and described the general

area. He and everyone described Milne

Inlet as a wonderful area abounding with fish, seals and most importantly

where the Narwhal go in great numbers to suckle their young. The Narwhal were what we had come such a

great distance to see. We knew that we

would be most likely to closely approach them in our kayaks as the kayaks are

unobtrusive. In Greenland Narwhal can

only be hunted with harpoon from the kayak.

In |

|

|

|

As out little kayak

armada departed from Pond Inlet, I took advantage of the following wind to

try out my Klepper drift sail. After

all, we might as well leave in style and not always are conditions going to

be so perfectly favorable. The prevailing

wind in the We were looking forward

to a long stretch of shallow near shore paddling along a gently sloping coast

line which could be landed on in most areas with sand beach areas. This coast was about twenty five nautical

miles long, a reasonable distance for resolving any problems with kayaks and

become accustomed do the paddling routine. After sailing about five

miles I became chilled. This is a

problem when sailing in the The bottom was shallow

and sandy except where the alluvial delta of the The Salmon River bank at

about 200 feet back from shore has the remains of |

|

clouds over |

|

As the trip down the

coast progressed to the southwest, the last point from which we could see

Pond Inlet was Tunuiaqtalik Point, about twelve nautical miles away. That point was the only distinguishing mark

on the south side of Eclipse Sound.

Across to the north we could easily distinguish the peaks and glaciers

of Lenticular clouds are

actually cumulus clouds distorted by powerful winds aloft which have a

distinctly greyer more compacted appearance than the adjacent clouds. Although it was a dreary day we were not

worried about being beset with heavy wind, we were probably receiving the

edge of a low pressure system to the east of us. As out little kayak armada

departed from Pond Inlet, I took advantage of the following wind to try out

my Klepper drift sail. After all, we

might as well leave in style and not always are conditions going to be so

perfectly favorable. The prevailing wind

in the We were looking forward

to a long stretch of shallow near shore paddling along a gently sloping coast

line which could be landed on in most areas with sand beach areas. This coast was about twenty five nautical

miles long, a reasonable distance for resolving any problems with kayaks and

become accustomed do the paddling routine. After sailing about five

miles I became chilled. This is a

problem when sailing in the The bottom was shallow

and sandy except where the alluvial delta of the The Salmon River bank at

about 200 feet back from shore has the remains of As the trip down the

coast progressed to the southwest, the last point from which we could see

Pond Inlet was Tunuiaqtalik Point, about twelve nautical miles away. That point was the only distinguishing mark

on the south side of Eclipse Sound.

Across to the north we could easily distinguish the peaks and glaciers

of Lenticular clouds are actually cumulus

clouds distorted by powerful winds aloft which have a distinctly greyer more

compacted appearance than the adjacent clouds. Although it was a dreary day we were not

worried about being beset with heavy wind, we were probably receiving the

edge of a low pressure system to the east of us. |

|

|

|

The next day we had

stronger, more threatening wind from the east of about twenty knots, but the

sun was showing. I paddled closer to

shore to avoid incipient problems, which might occur with this amount of

wind. I really don't like rusty hair

pins. My friends in their Nautiraids

happened not to have brought drip rings for their paddles. They were uncomfortable that day as plenty

of water ran off the paddle shafts onto them.

We should have invented some sort of drip rings, Even an ordinary

piece of line tied around a paddle shaft will work as a drip ring. We pulled into shore for

the evening behind a cluster of melting grounded-out pans of rotten ice which

covered the harbor leaving but one access to shore. The ice was pan ice from last year melted

to the state which is called either rotten or brash ice. This ice is highly crystalline, loosely

structured, very weak, about eight feet thick, fresh water, severely undercut

by seawater at the mid line, thus it is constantly collapsing and rolling

over if it is not grounded. This annual ice is

unstable and is actively disintegrating.

You cannot expect to run up your kayak onto it or get out onto

it. It would crumble under such a load

stress. If multiyear ice is

available often if it is large enough you can get away with landing on it and

drifting around on it but you do run the risk of the chunk of ice drifting

into a mass of ice chunks. Polar bears

ride multiyear ice chunks. Annual and multiyear ice

is not anything like icebergs that are constantly changing their center of

gravity making them completely unstable. We carefully chose our

campsite considering the bears, but I would have preferred that we camp else

where access to the water was not so limited by ice and where polar bears

cannot so easily hide. Not only is ice

white but so are polar bears. My friends cooked over

driftwood which was planks from packing crates brought by ship into Pond

Inlet. I cooked on my trusty old Svea

123. Never have I had a problem with

the Svea that I couldn't resolve. I

like simple straight forward equipment especially a stove. The Optimus,

Primus and Svea stoves have been around for a very long time. Shackleton and Nansen as well as many others since the 1890's used these

stoves. |

|

08 |

|

Marshy groundwater and

snow meltwaterin this area of the My only explanation is

that the aquifers must be in an upended strata

similar to the Here I tried to maintain

dry feet by using my waterproof shoes and Gore-Tex socks. I did happily survive

with somewhat dry feet. The Gore-Tex

socks were an experiment but I thought "nothing ventured, nothing

gained." Our first day of paddling

was the most monotonous because conditions were not challenging and the

scenery was either of low profile or too distant to seem exciting. But we knew paddling would soon become

exciting as we could see from the topography of the fjords and islands we

were going to be encountering soon enough. |

|

Fulmar with wings outstretched |

|

We had a lovely evening

with local flora gathering, cooking and eating. We ate a salad of leaves of a plant in the

Oxyria / Dock family. Their leaves are

round, very tender, dark green and especially high in vitamin A. Dock leaves are so high in Vitamin, I was

afraid to eat a full bowl of them. We picked mushrooms and

added them to our evening fare. I

saved some to sauté with my eggs in the morning. I found that powdered

eggs are tasty in the morning and most importantly they have completely

balanced protein. If I had been

concerned about cholesterol intake, I would have found a comparable

substitute without cholesterol, because breakfast with insufficient protein

soon catches up with me. We cashed our food away

from our boats and tents not wanting to attract polar bears. We found it was best to just keep a routine

of retiring for the evening at Because the light is

sufficient in early August all night travel sometimes at night the weather

will be calmer. The wind that is

generated by bright sunshine may stop blowing and you can paddle in these

better conditions. Katabatic winds can be

generated by bright sunshine and can be very powerful. |

|

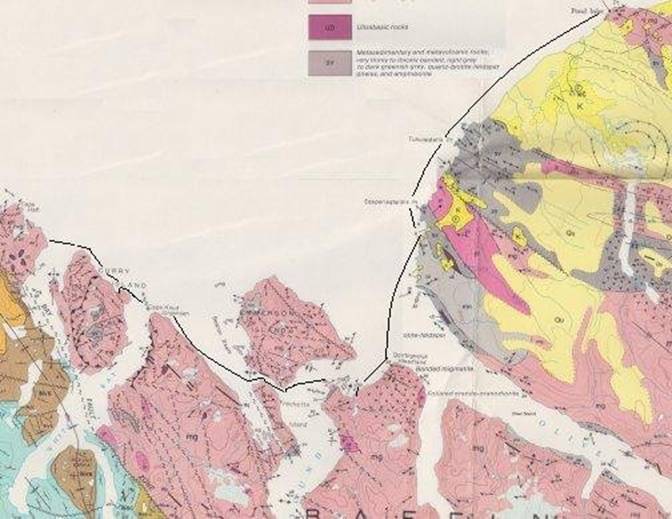

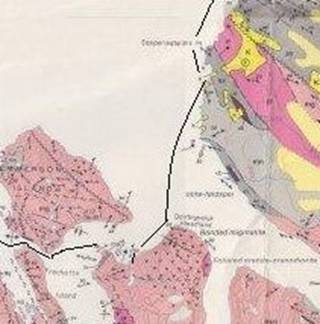

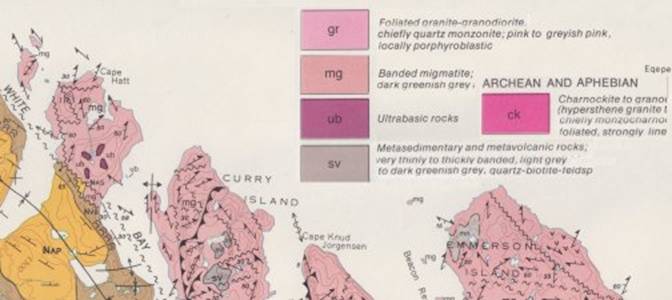

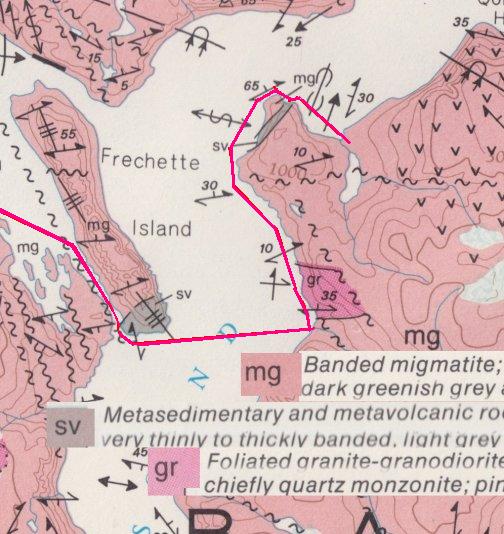

On our way down the coast

heading south we stopped at this area and found these rocks. Below is a photo showing

the very interesting metamorphic rocks found in the area just southwest along

the coastline from Pond Inlet. I

enjoyed the colors and striations on the rock. I was really looking forward to paddling in

this area to see some more exquisitely interesting rocks. |

|

|

|

Some close up detail of metamorphosed rocks which I found. |

|

|

|

This is a very amusing moment when an ermine came out and ran over

these rocks. |

|

|

|

I could not believe my eyes when I saw this creature running down the

rocks. There he was in summer pelage

out and about looking for food. |

|

|

|

This ermine was so busy he never noticed my presence as I stood there

trying to barely move as I quietly took these photos. |

|

|

|

Our second day had been

very windy from the east and partially overcast. As a conservative paddler I suggested that

we keep together as a group and stay close to shore which was to the east of

us. With this offshore twenty to

twenty five knot wind I felt that a boat blowing away or capsizing would be

wise to avoid in these cold waters. I

was glad that we did not have to risk any paddling exposure greater that this

today. It was a good test of

judgment. I recognized that the waves

are much smaller on cold water for the same amount of wind as compared to

warm water because cold water is reacts more slowly to wind. The water in this area stays within five

degrees above and below freezing throughout the year. By the end of our

paddling day the effects of the cold water running down the paddle shafts of

those who did not happen to have drip rings made paddling a wet cold

ordeal. We cut short our day and found

a campsite on a rocky shore behind some chunks of brash ice. With a bustle of campsite preparation a

quickly made hot fire we made our usual hot soup appetizer, which immediately

came to the rescue. Once again we were

warm and relaxed. We ate some more

mushrooms, which we found and saved some for breakfast. In the photo below you

can see three double kayaks. We had at

this point just taken off from Pond Inlet.

You can see the coast line is very low but when you look at the

background you can see some of those mountains where we are planning to

paddle. Those mountains are in some

instances just straight up and down 3 and 4 thousand feet high. |

|

|

|

We knew that if the wind

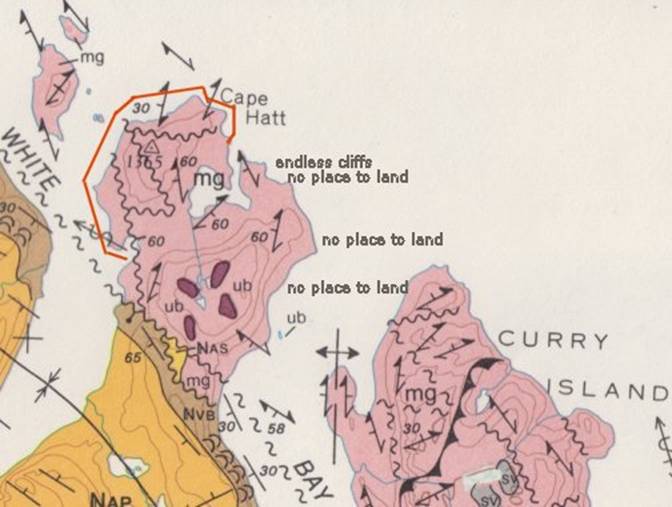

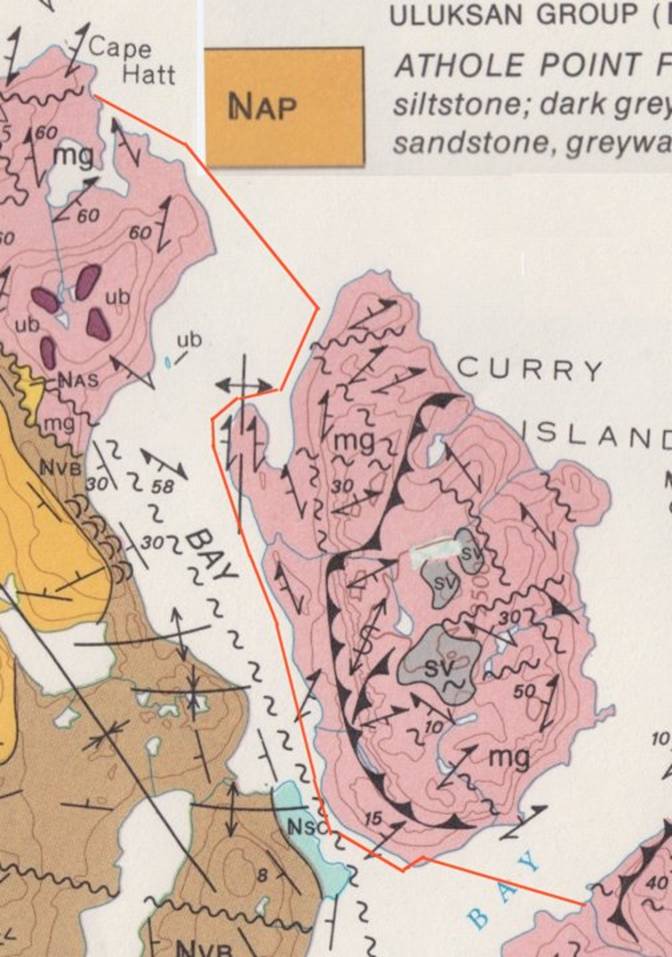

subsided we could make our crossing of This would be a four mile crossing with no place to land because the

slopes of Qorbignaluk Headland and |

|

|

|

We had been advised that

we must not attempt to cross unless we had calm conditions. As luck would have it we awoke to a nice

morning to make our crossing. From

where we were located on low lying land we were about to approach the

mountain cliff faced fjords so famous.

All we knew was that we were about to encounter our first experience

in paddling among mountains. As you can see above on

our third day we could see |

|

|

|

From what we could see as

we looked to our south down Oliver Sound we could see that there were many

other similar cliff faces lining both sides, appearing as though Oliver Sound

had been cut out just like one cuts out a piece of cheese. We felt very small, for

indeed we really were when we were next to these escarpments. We realized that we were about to enter a

much more challenging kayaking situation, one in which we would not have

continually available landing places. |

|

several thousand feet straight up and

down |

|

In this is a typical

kayaking situation one appreciates good equipment and being associated with a

group, which has some double kayaks.

You realize that you must be very aware of conditions and everyone’s

capabilities. We had no definite

knowledge of where we could even land; much less find an area large enough to

camp, but I concluded from our topographic maps that most river and stream

beds might be useable. These cliffs were so high

that the nimbus layer of clouds would form a ring midway up them, as this

level of clouds are the lowest level of clouds. A remarkable quality in the Against the 6,000 foot

mountains of |

|

|

|

Local people had warned

us not to cross |

|

|

|

At this stream we found

what were likely to have been the remains of a fish weir for trapping char. We had previously chosen this place because

the stream was fed by a lake, which we knew char would live in for part of

the year. The remains of what appeared

to be an extensive semicircle of rocks encompassing all but a narrow

midsection of the mouth of the stream.

The semicircle having about a hundred foot radius. On the west side of the

stream we found an extensive array of dwelling remains from recent stone

circles which were tent circles to much older structures representative of

some of the earlier cultures. These

stones were used to secure walls of hide tents. The age of the stone circles could be

estimated by the amount of lichens growing on these rocks, the more lichens

covering the rocks the older the tent circle.

Some circles had hearth remains in them and others were keyhole

shaped, having a defined entrance.

Still other circles had combinations of intersecting circles. Even more fascinating then

these tent circles were the remains of single and double level sod and whale

bone smaller houses dug into the stream bank.

This was not nearly as common to find as tent rings. These dwellings were tiny, but intricate by

comparison to the tent dwellings, suggesting that this area must have always

been a good place find fish and game.

Franz Boaz describes some of these types of structures in The Central

Eskimo. This area is probably used

extensively when the Inuit can travel in boats and when ice has formed thick

enough to be crossed with sleds, but approach from over land would be a very

long trip. |

|

|

|

As we made camp we found

that this area was an acidic peat bog with blue berries, more mushrooms and a

special herb called Ledum, which had a resin that made its tea smell and

taste slightly like eucalyptus. It was

in the laurel family of shrubs, not very common and quite inconspicuous. Along the beach margin Arctic willows grew

over the rocks and among the crags strictly limited to espalier in the slightly

sandy soil. Below is a photo showing

Salix willow growing flat over the soil.

The pink flowers are Epilobium or fireweed which is edible as a salad

herb. The surface of soil is

covered with low growing dark green mosses. |

|

|

|

There was water all over

the place and endless moss, lichens and tiny pincushion plants such as this

Moss Campion in the photo below. Note the short grasses

and sphagnum moss here and there. The

white and gray splotches on the rocks are forms of lichens. You can see tall forms of lichens in the

background which are cetraria and reindeer lichens. These lichens prefer acid soils. There is a clump of Sedum right of center. In the water are dark forms of bluegreen

algae and mosses. |

|

|

|

We gazed across the

channel at the pink streaked grey cliffs of We ate another nice

dinner complete with soup and ending with several cups of Ledum tea. Then we let the fire die and watched the

evening close behind |

|

Our fourth day was an

idyllic summer day, bright and balmy.

We paddled along the western side of the cove, which we had camped at,

enjoying the endless swirls of quartz and both white and pink feldspar

striations in the charcoal grey gneiss.

|

|

|

|

The swirls of minerals

became so fine that they looked like cotton candy, something which seemed

absolutely extraordinary to me. We had

a wonderful time gazing in the clear water looking for Sea Urchins, which we

would have been delighted to gather for later consumption. We saw the loveliest

Ctenophores which are called Box Comb Jelly Fish and look slightly box shaped

having two wonderful three foot long tentacles that stream behind them in the

current to catch food but can be completely retracted when necessary. We saw another ethereal looking jellyfish

called a Medusa. |

|

We then started making

the crossing toward the southern |

|

|

|

These grey cliffs had wonderful wide bands of feldspar and other

layers in them. |

|

|

|

We were on our way west

to the northern tip of We no longer saw any Sea

Butterflies, which we had seen millions of in Pond Inlet. The Sea Butterflies are Pteropods, a type

of Mollusk that swims. Of these

Pteropods there are two types; one was a long tadpole shaped mostly clear

with orange spots and little flipper-like wings and the other was solid black

pill shaped with black little wings. Below is the clear one

with orange coloration. |

|

|

|

These creatures occurred

often in large swarms near the surface and I believe the Fulmars ate large

numbers of them. They are also food

for some Whales. |

|

|

|

We were happy to have

arrived none too soon at In the photograph I am at

the |

|

|

|

We had the company of a

stranded iceberg at our lunch place and some sand and rock shoals not noted

on our nautical charts. I guess nobody

expects any oceanic vessels to be calling at |

|

|

|

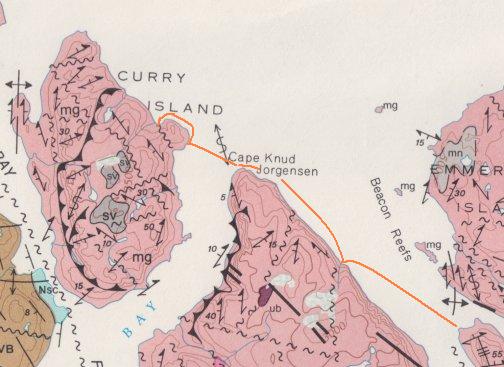

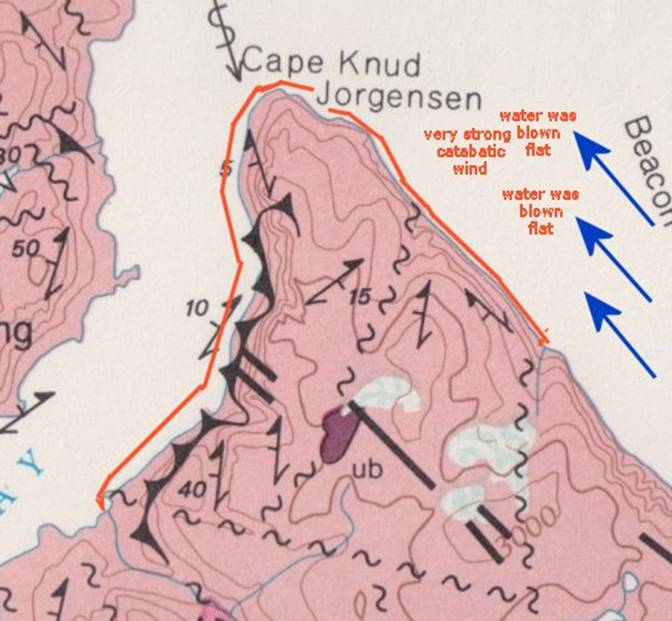

To our west for a

distance north of about five miles lay Cape Knud Jorgensen. What immediately caught my eye were the

cliffs. Although they ere the same

height of about 1,500 feet as the topography we had to our east from which we

had just come, they had the distinctive appearance of being sedimentary rocks

most likely of sandstone. They had very definite

straight stratification in these layers.

At the bottom of these cliffs were talus slopes extending up these

escarpments a long way, almost twenty to twenty five percent of the cliff

face. Only soft sedimentary finely

layered rock cliffs have this weathered appearance. I also thought we could easily have a

shower of these rapidly disintegrating rocks come down on us at any time if

we were to venture too close to them.

Massive rockslides are easily set off from this type of rock. I did see a rock slide let loose on

Qorbignaluk Headland from the 3,000 foot level and it was most

impressive. I was glad I did not

happen to be passing by that area at that moment. The rock dust from that rockslide hung in

the air for twenty minutes. I felt

very small. From the top of Cape Knud

Jorgensen came three waterfalls, each more grand than the previous, as tons

of water hurled itself down the cliff face.

The aquifer feeding these waterfalls must have had some extraordinary

artesian pressure. At the base of only

one of these waterfalls could we possibly land in this expanse of five

nautical miles. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

As we rounded the tip of Cape Knud Jorgensen there were a few landing

places but not very suitable for camping. |

|

|

|

I looked for the Beroe

Ctenophores in this area of Eclipse Sound, which I had seen in large numbers

in Pond Inlet. These Ctenophores look

quite different than the majority of others, because they spread their mouths

into an umbrella shape with which they capture food by opening and closing

repeatedly. They are often stranded on

shore where they look like clear orange pink almond shaped Jellyfish. They have no tentacles like the rest of the

Ctenophores have. |

|

|

|

These

Plankton were being transported on the rapid current which sweeps around |

|

We could see lush green

areas of tundra across Fearing that someone

might accidentally slip into the frigid water when negotiating a landing on

the available inclined smooth rock face I suggested that we proceed further

west along the coast of Curry Island where most likely there might be a

campsite, because on the topographic map two streams were indicated. I was just taking a guess and we were all

starting to feel tired. I was glad

when we finally found the stream that was illustrated on my chart. There was no way of

knowing for sure, because our maps were not detailed enough to show the

inclination of the last few feet of land at the water edge was. Our campsite faced northwest from which

after preparing camp and eating dinner we were treated to a brilliant sun set

at |

|

|

|

Actually, since we were on Eastern Daylight Savings Time, the true |

|

|

|

The next morning we got underway on our fifth day heading west

again. We passed the other campsite on

the north Then we found as we were

rounding the northern tip of |

|

|

|

We crossed the western

arm of |

|

|

|

A couple miles after

having rounded |

|

|

|

We encountered a bright

yellow extensive low profile multiple layered stony and yellow sandy beach

and the accompanying shallows. The most unusual quality

this beach had was its size both in width and depth and the very clearly

defined layering which extended as much as thirty feet above sea level. It appeared to me as though storms would

drive the water carrying stones and sand up the beach, leaving these deposits

when the raging waters subsided. I

really didn't want to camp there with menacing aspect visible. Rounding a rocky

peninsula, we spotted an area, which looked safe and protected for

camping. Finally I had a favorable

wind for some downwind sailing and that's just what I did. After twenty minutes my teeth were

chattering. I was glad when I finally

made land. I was quite cold. We prepared camp, ate dinner and explored

the first sand beach we had seen in days. |

|

|

|

I thought it was curious

the amount of pink stone in this area probably due to iron. The color of pink feldspar. |

|

|

|

Pursuing my old interest

in contemplating natural phenomena, I noticed something very odd. Why on earth were there large amounts of

lime green clumps of filamentous algae growing in the brooks? Why were there extensive areas of all sorts

of grass growing everywhere? Where

were all the mushrooms and familiar acid soil plants? Some strange lichens were growing

here. The ground lacked the deep soft

spongy feel of a peat bog and the water was not tinted brown from tannins

leaching from peat. I had the feeling

that we were in a limestone area and indeed on the next day, which was too

windy for boating I found heavily eroded limestone. The photo below is poor

but it does show the limestone with iron included. |

|

|

|

There also was a capping stratum of granite, which occasionally

harbored areas of acid soil plants. |

|

|

|

This was the first

granite I had seen on These are the first Arctic

chrysanthemums I have ever seen the flowers are one inch diameter on three

inch stalks of brilliant white with gold centers. |

|

Chrysanthemums |

|

Among the granite I found a Woodsia fern which grows in Arctic areas

in granite ravines and crevasses. This

fern was so tiny that it had fronds only one inch high. This was the only fern I was to find. In the photo below the pale green plant in

the center is the fern. In front of the pale

yellow Woodsia fern is Dryas or Mountain Avens and in back are the large

Cladonia or Reindeer lichens. |

|

|

|

These rounded polished

granite rocks were much different that the other jagged metamorphic and

sedimentary crumbly rocks in the area.

We even found fossils of bivalve Mollusks in the limestone. |

|

looking north to Bylot and Navybord inlet |

|

From atop the knoll I

could see the shimmering blue passage behind |

|

looking south |

|

My friends decided that they would prefer to head back to Pond Inlet

with some extra days available in case of poor weather, which was a good idea

because the weather here changes very quickly and we could become wind bound

very easily. |

|

We were fortunate enough

to be given an Arctic char by some local hunters across the bay, which they

had caught in a net. It was very kind

of them to share their catch with us.

This was a wonderful experience in delicious eating after careful

baking with spices in aluminum foil over the fire. I only wished we had burned Arctic Heath

instead of wood as Arctic Heath gives a special flavor all its own to food

cooked over it. |

|

These local hunters also

warned us about Polar bears, which gave credence and plausibility to my

knowledge about Polar bears. It was

nice to, at long last, not be the only one carrying a functional firearm and

taking care not to leave any food in my boat at night. As for the layout of our tents, the bear would have six tents to

choose from, but at least we had no food in them. So as to not lure the

possible bear visitor, we did our cooking and toilet far away from the tent

site. We were all very smoky smelling

from our numerous wood fires, which is and odd odor to an Arctic animal. Bears are generally motivated to visit

campsites by curiosity and unfortunately we had generated more than our fair

share of curiosities. It is best to

smell as human as possible. You are probably

wondering where did this wood come from which we

were cooking with. There are no trees

in the |

|

Now on our seventh day the wind still blew and on the grey horizon to

our west I could see lenticular clouds.

My friends decided that we would that we would leave on that day to

return to Pond Inlet anyway. Below is a photo showing

our situation which is actually taken later in the day. |

|

|

|

I was glad I had my dry

suit and that I was in a Klepper. I was

scared and had the thoughts of "Don't call me, I'll call you." but

we launched anyway. The familiar

saying "You can lead a horse to water but you can't make him

drink." when used in this situation would be "You can lead a

kayaker to cold water, but you can't make him think." applies in this

instance, because and Chuck Sutherland so often noted "Cold water

kills." These people from These new friends from |

|

|

|

I knew one thing; and

that was when we rounded We hauled up off the

rocks on the point to take a gander of what was next. This is roughly what it

looked like – just a completely charming situation. |

|

|

|

All I knew from my past

experience was that the wind was just too much. I decided that I would split off from the

group and duck into the nearest area where I could land. Well, that was exactly

what happened; I started out ahead of everyone and ducked in at the nearest

stretch of sand. When I turned around

to find that everyone else had the same idea.

The rest of the group was

following me. It was supposed to just

be a lunch stop, but we were not interested in any more punishment by the

wind. Our narrow beach was just wide

enough to accommodate our boats. We

staggered up the steep knoll and set up camp, just too exhausted and scared to

do anything else. After some very careful

scouting we found a very tiny spring in the rock and clay bank, which some

thoughtful person had marked with a stake, this made me feel that we weren't

the first people to become stranded here.

The spring was tiny and filling the water jugs required great

patience, but it was the only water we found, so that was a small price to

pay for this precious commodity. I found some

extraordinary green and red metamorphic stone here. Some of it was, I believe, olivine,

pyroxene, tourmaline and malachite.

The colors were brilliant. I am

not sure what these rocks were. I

should have taken some samples, but the thought of extra weight was the

limitation. Below is a photo I took. |

|

|

|

As I was resting in my tent the came call out

that Narwhal were swimming by. I took

pictures as the pod of about one hundred passed by heading for Milne

Inlet. It was such a precious

experience not only to see them but to hear their rhythmic breathing as they

synchronously surfaced. It is hearing

the breathing of a sea mammal such as these Narwhal, which made me feel close

to them as fellow mammals. |

|

Had I not decided to duck into this beach we

would have never seen these Narwhals. |

|

|

|

Our eight day was crowned with sunny balmy weather. We rounded the eastern tip of |

|

On the water there were sandy shoals and we could

see the bright yellow, the color of Limonite, sandy bottom. We relaxed and

entertained ourselves looking at the panorama and cutting in and out around

the rocks with our kayaks while peering at the bottom and basking in the warm

sun. We disembarked at a

recently abandoned sod house area, both new and old structures. Here we found the recent

remnants of occupation such as tin cans and modern wood flooring. It was a warm sheltered area, easy to land

at by boat of skidoo because it faced south and was on a gentle slope. |

|

|

|

I found plenty of blueberries to eat on the

hillside, but we never found a water source, which may have been a habitation

limitation, making this site only useable when snow was on the ground. We headed east across the

eastern arm of White Bay for a green valley, which was now awash in the long

rays of the warm afternoon sun on the western side of Cape Knud Jorgensen

where we were to camp. We finally decided which

side of a stream delta was best after realizing that what seemed to look easy

was a long and difficult carry over many boulders to get the boats above the

tide line. We found the north side of

the delta to be shorter and not nearly as boggy. We also found recent Caribou prints and

other residues. This was our first

encounter with Caribou and we were delighted to at long last have found

them. We found some antlers, but they

were much too large to consider taking back. |

|

|

|

The stream, which ran down the hillside, had been

warmed by the brilliant sun on the dark peat soil enough to allow for a quick

sponge bath. My body had started

sending me messages such as "wash me or I will itch" most particularly

my hair. Before I had left I used it to soak up the

tiny amount of water that would seep into the bottom of my kayak but my most

important application was for drying my hair. I found that I could dunk

my head in the frigid water and wash my hair with an all purpose soap called

H2O Sun Shower Soap which was suitable both for use in salt as

well as fresh water. Well, to my

delight both the soap and towel worked to my great relief, I felt as though I

had returned to the world of the sane once again. On a previous trip, dirty

hair became very distracting as my scalp more and more urgently kept telling

me "I'm dirty, I don't like being dirty, I'm leaving." as the

itching increased. I do wonder though

how does one wash their hair in a space ship in a weightless environment? On our day nine heading

in a roundabout way home to Pond Inlet, once again a grey sky with mixed

clouds to the west showing some more lenticular clouds indicating strong wind

which was coming from the south, we set off to round Cape Knud

Jorgensen. We made the |

|

|

|

My naive friends blithely set off for possibly

the only landing point five miles south into a very powerful south wind which

was katabatic in nature. The wind was

not blowing horizontally, instead, it was blowing

vertically so that it blew the water flat.

|

|

|

|

Later upon consulting with a meteorologist, Hermann

Steltner, at Pond Inlet, he said that this does happen in this particular

area. As we worked our way down the

coast, hugging the cock cliffs to avoid as much as possible the inevitable

exposure to this fierce wind. There was no doubt in my mind that this

endeavor was not only futile, but courted disaster. Not only was making the nearest known

landing place which was five miles away impossible but trying to turn kayaks

180 degrees in this wind could easily result in a capsize of a kayak. Kayaks are very stable going into a wind,

but when run with the wind they do not have the same stability. The paddling became very strenuous and this

extreme amount of exertion could give a person a heart attack. I could barely move my boat. It was everyman for himself, a dead heat

battle. Then I noticed something

out of context. The leading boat was

making for a landing at the base of a tumultuous cascading waterfall, which

had a tiny area just large enough for landing a kayak one at a time. I had

noted this disembarkation area when we previously by on our way

westward. This was our only chance

without having to risk turning around. From the water this site

looked challenging for camping by appearing only to be a steep side hill

punctuated by massive boulders. I quickly alighted from

my kayak, tent in hand, not waiting for protocol and quickly found a

reasonable tent site. Erecting the

tent in this wind required the judicious use of rocks strategically located

to keep my tent stakes in the ground and the tent upright in this mad

wind. I was glad I had taken my above

timberline tent on this trip. My feelings about the

discretion of not only the leader but of the group I was accompanying I

thought was best expressed by Scott Joplin in his music. Whew! |

|

|

|

The next day the weather was as somber as a tomb. We leisurely paddled south past To my left, which was

backlit by the brilliant |

|

|

|

I decided to cross to |

|

Passing next to the vertical rock faces of |

|

|

|

Very suspiciously there appeared an odd arrangement of small boulders

across the dead flat water, which I happened to notice that stretched from |

|

|

|

Little bells went off in

my head, "something tells me that this is a very shallow spot about to

become exposed as the tide is now reversed and some of those small rocks look

like there isn't much water around."

Quickly I jumped out of my kayak, grabbed the bow and deftly "hot

footed it" dragging my kayak with just barely enough water to float it

across this strategically placed sand bar.

A few minutes later and I would have had to unload and carry

everything across. You never saw

anybody as glad as I was when I got to the other side, because in the next

instant the passage was dry. The

scenery was nice, but I was not in the mood for the tide to fill back in so

that I could float my boat. Whew that

was a close one! My friends got there

too late and had to carry their boats across.

Funny thing though, When we had stopped for lunch I just felt like I

should keep going, never imagining that the tide would create this situation. |

|

|

|

I wonder if that could have been a possible fish weir because the

placement of rocks seemed more likely to be the work of people that nature. |

|

Now I was faced with my first solo Arctic crossing. I was crossing the eastern arm of Tay Sound

in bright sunshine with completely benign conditions. |

|

|

|

I was not at ease about

this but this crossing was not only a paddling event that I could do but that

I had to do for myself. Sometimes fear

is not a good thing! But at long last I got to the other side. The crossing seemed to

have taken ages, but it was just a routine crossing. It is interesting how anxiety can make time

take so long. I stopped at a brook for

some nice fresh water, and there as I was leaving I spotted some delicious

Green Sea Urchins, large enough to eat distributed all over the submerged

rocks. I decided that I was going to

enjoy these tasty morsels in style. I

never passed a Green Sea Urchin I didn't like. My idea of style for sea

kayakers is that one should be grabbing and enjoying their catch while sitting

in the kayak. I decided that with a

little paddle juggling I could pry off the rocks my Sea Urchins, place them

on a flat area, smash them open with my paddle, and devour their gonads

material, which is orange egg shaped balls in the top of the shell or

test. Well it worked, and I dined

without candelabra - the sun was shining.

Actually you can leave the candelabra home, because it is never quite

dark enough in the |

|

I progressed along the fascinating

endlessly complex metamorphic gneiss in charcoal grey being awe inspired by

the never ending interwoven striations of white and pink feldspar resembling

cotton candy swirls. |

|

|

|

Quietly paddling along my

solitude was broken by the splash of a curious seal from behind me. Luckily I had experienced this before off

the coast of Once again I arrived at

our old campsite behind Qorbignaluk Headland on Tay Sound, where we last were

on our fourth day. About an hour later

after I had found a pleasingly soft, level, slightly dry campsite and set up

my tent I heard the familiar voices of my French friends. |

|

our tents with clouds over head creeping downward |

|

In the Arctic one does

not find dry soft areas as the softer they are the wetter they are too. They had been following

me after they had eaten their lunch. Unfortunately when they

arrived at the southwest tip of However after they

crossed Tay Sound they also found the same treasure of Sea Urchins I had

found, which they gathered in a bag and we dined on these as an evening

appetizer. Wow that was good! Nothing like eating some Uni freshly gathered

from the water. |

|

We had a rather innocuous

evening when we retired, however the next morning our eleventh day which we

had planned to rest and do some hiking for a change, turned out to be a

stagnant day for the weather |

|

another view of the clouds creeping up and down |

|

A rainy foggy storm,

which was a small stationary front, just hung in the air over us trapped in

this area and I could see five miles away another weather condition. I later learned that this can happen in

this area of fjords. We had

cumulonimbus clouds stuck so it seemed in our valley at about 1,000 feet on

the back slope of Qorbignaluk Headland. Here we could have pretended that we

were angels and St. Peter in these clouds just by walking in and out of

them. We spent the day relaxing and

exploring. |

|

|

|

Our twelfth day was

slightly windy, just ten knots, and we had bright sunshine. We crossed |

|

With the tide receding

and a light headwind I left my friends once again heading back to Pond Inlet. Being alone along this coast I knew was

unlikely to be dangerous, because I could land anywhere most of the way

back. There were no high cliffs, instead there was just a low sandy terrain. The possibility of finding a polar bear was

not likely in this area. |

|

|

|

The wind stopped

blowing. The tide assisted me as hour

after hour the miles went by. Being

alone I encountered a flock of Snow Geese at close range which I forgot to

record on my Cam-Corder. The water was

clear and the gravel and rocky bottom was colorful and interesting to

study. The only ice around were

occasional icebergs here and there in the shallows across the bay about

twenty miles away. I passed a large hunting

camp on a point, which had a few large tents. As the evening hours approached, a number of motorboats passed by heading in

the direction of the camp. Other motor

boats headed out to the west for |

|

|

|

At any one time you can ask a person where someone is in Pond Inlet

and it is very unlikely that person does not know another person's

whereabouts such as what camp they have gone to. But when it comes to time that is a

different concept. The Inuit do not

adhere to a time schedule but do traveling and tasks when they feel it is

appropriate. Sometimes this can be

difficult to relate to; but when the sun just keeps circling around twenty

four hours a day, time seems absurd. |

|

looking across at |

|

I found an expansive

sandy beach to land my kayak on and prepared camp. Now the motor boats were passing by so

frequently that I decided that I must have arrived at "Broadway and

42nd. Street." I didn't have to even consider that I was alone. As I was cooking dinner in the long orange

rays of the waning sun suddenly I found that I was being visited by a curious

Arctic fox. I was so completely

surprised that I did not even think to try to take some pictures of him. He danced and pranced on his toes around my

Kayak, inspecting everything. I had

not in my wildest imagination thought that an Arctic fox can be this precocious. I had read of this trait in Arctic foxes,

but I did not think that it would be likely I would encounter such a

fox. The only other wild animals I can

think of which are similar in personality to the fox are ravens and seals,

which enjoy heckling people especially campers and kayakers. I slept well and awoke to

a bright sunny thirteenth day. After a

leisurely breakfast, with two cups of Italian coffee no less, I launched for

the final push to Pond Inlet. It was

brilliantly sunny, a dead calm and then there came this soft wind from the

west generating gentle swells more widely spaced that they were high, which

had the character of ground swells.

These gradually increased in height as the wind blew for a more protracted

period. I came upon a shoal beach with

outlying islands, which seemed to enlarge these swells. As these swells

became restricted by the confining shallows, they were forced to crest and

break. Luckily the beaches were

varied enough so that a protected area could have been found if necessary. The water was just rolling but flat until I

noticed in the distance a darkening on the surface of the water. I just thought that it might be a color

difference because of a current since I was working my way up and around

beginning to head more and more easterly toward Pond Inlet where I knew there

was a distinct tidal current, which I had become aware of when I paddled

against it. |

|

|

|

Well, that darkening of

the water at a distance gradually drew closer and closer until it was upon

me. Guess what, it was caused by a

freshening wind coming from the east. The wind from the west,

which had generated the long swells dissipated and now I had wind in my

face. The cloudless sky had given away

to increasing clouds. Paddling became

interesting as waves from the east which were a short chop would intermingle every so many sets with a ground swell from

the west, some thing familiar to me in Long Island Sound paddling conditions

on occasions. The waves had a rhythm of

about three sets from the east and one roll from the west, which I took

advantage of, to make some progress against the wind coming from the

east. And as the wind speed from the

east increased the more ardently I paddled my craft, working harder and

harder to round one of the large unnamed points, which seemed to separate

east from south in Eclipse Sound and Pond Inlet. Now the tide had changed against me. I thought I was never going to see the last

of this unnamed point. I found that I

was engaged in treadmill paddling as I was inching my way eastward. I just did not want to give up. And so I plodded along the shore as the

time passed by. Finally as I had made

progress enough to see the town of |

|

When I found a suitable

ravine I took advantage of the intermittent larger swells to bring my Klepper

up as high on the beach as I could without having to carry it. Then I unloaded my boat, picked it up and

carried it up to the ravine. The

ravine had enough area to set up my tent and I enjoyed its shelter while the

wind pummeled the rest of the grey world. I slept and dozed in my

tent like a bug in a rug. Then I awoke

to find the sun peeping through the clouds.

The storm was subsiding. I

found that I could not ignore the brilliant yellow rays of the sun, and so

with renewed energy, I decided it was time for a celebration cup of my favorite

Espresso and some dinner. Further up in the ravine,

which I was camping at the mouth of, I found a protected cooking area. I gathered some water, which was also

conveniently available. Ah! Nothing

like a good cup of espresso to make a party. As I was waiting for my

espresso to erupt in its usual fashion in the pot, I glanced up to gaze at

the opposite side of the ravine when suddenly I saw an Arctic fox standing

there only about seventy five feet away.

I was shocked to see this little creature sniffing the wind trying to

figure out what I was doing. Then he

paced over to my left but a little closer and sat down. I had to watch the stove and coffee pot,

but that did not disturb my very curious fox visitor. Then after sitting a few moments the fox yawned,

as if bored in general, and then proceeded to scratch an itch behind his

ear. Some shedding hair came out of

his tan and brown coat as he scratched; and then just to be thorough, he

shifted to the other side to scratch that side. He paused in his toiletries to watch me

some more. He got up again and

resituated himself, this time to my right and a little closer and once again

resumed his toiletries of scratching and some more yawning. I shut off my noisy stove and dared to pour

myself some coffee, which didn't disturb my guest in the least. He could stand his curiosity no longer and

walked directly to within six feet of me, when in fear that he might be rabid

I shooed him away. He turned and ran

off continuing his endless tour of the tundra. I thought he might return of that I could

relocate him later, but after much walking and looking I found that he was

gone. All of this took place

and I did not dare to get up and go get my camera. Now in retrospect had I known that a fox

might have as tame as this one was, I would have taken the risk. He did not run away until I actually shooed

him away. I found that my encounters

with foxes took place when I was cooking and probably when cooking it would

be wise to have the camera available. |

|

Now that the wind had

died down and I felt energetic, I broke camp and headed for the I had the low tide

running with me, but I had to cut a wide berth of about a mile off shore to

avoid the shoals of the Salmon River. Happily I arrived back at

Pond Inlet at 11:00 p.m. as it was beginning to grow dark and the frost was

coming. This photo below I took

holding my video camera just above the water to capture the light on the

waves in this sunset. I wanted to capture what a sunset looks like from a

kayak at water level. |

|

|

|

The next day my friends

arrived and I made a day trip to My friends told me that

they were frightened that this pod might be some Killer Whales, how lucky I

was that they were seals. |

|

|

|

I took this photo from the shore of Bylot island across from the bay

just before Mount Herodier. |

|

|

|

As I arrived at Mount Herodier the cargo ship from Montreal arrived. |

|

|

|

|

|

I turned around for my last paddle to Pond Inlet and who knows when

you take pictures and videos what you might get to tell people years later on

the internet! |

|

|

|

Gail E. Ferris, 1 Bowhay Hill, |