|

Wind, Waves – Kayaking; And the Water

Was Blown Flat Gail

Ferris – gaileferris@hotmail.com It is a good idea to find out what the paddling

conditions and situations are before you arrive with your kayak in an area

that you have never paddled before, especially what the wind is like and how

the ice behaves. I find that as an experienced kayak paddler that

I shall never become so completely experienced that I can just go paddle

anywhere with complete confidence that nothing threatening will happen. |

|

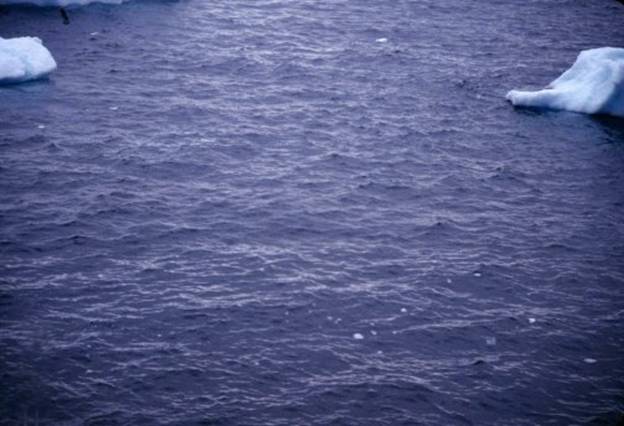

A few days after a storm in 2003 off Upernavik

Greenland waves from a residual wind made the water look like this from my

kayak bow. I took advantage of the

wind behind me to run for twenty miles on the backsides of the swells and

waves down wind. I felt as though I

was just having an effortless paddle with little to worry about because I

could relate to the strength of the winds by what I could see of the waves |

|

01 |

|

Below is a photo of crisscrossing waves which I

happened to notice while looking out at the water. |

|

02 |

|

I have encountered situations where there were

no waves but instead the water was absolutely smooth and did not indicate any

wind. In my account of paddling in Pond Inlet on On day nine heading in a roundabout way home to

Pond Inlet, once again there was a grey sky with mixed clouds to the west

showing some more lenticular clouds indicating strong wind which was coming

from the south. We set off first

heading north along the west side to round Cape Knud Jorgensen. We made the tip of Cape Knud Jorgensen without

much effort because we had the wind behind us. Since the wind was coming from the south I

knew after we rounded the cape heading now south that we had the makings of a

difficult day. My paddling companions blithely set off from the

tip of the cape that they had just made with ease. Now we were all were heading south directly

into the wind on the east side of Cape Knud Jorgensen. Sure enough from the south was coming a very

powerful katabatic wind. The wind was

not blowing horizontally but in this topographic situation, the wind was

blowing top down so that it blew the water flat. From my kayak I could see absolutely no

waves at all. I was shocked to think

that there could be such a thing as wind blowing is such a way as to blow the

water absolutely flat. Usually from my kayak I expected that I could

see the wind as indicated by waves.

However as I found out this is not always the case. Indeed the worst wind can be a downdraft

where the water is blown flat. As we worked our way down the coast, hugging the

cock cliffs to avoid as much as possible the inevitable exposure to this

fierce wind, there was no doubt in my mind that this endeavor was not only

futile, but courted disaster. Not only was making the nearest known landing

place which was five miles away impossible but trying to turn kayaks 180

degrees to return to the tip of the cape in this wind could easily result in

a capsize of a kayak. Kayaks are very stable going into a wind, but

when run with the wind they do not have the same stability. Paddling became very strenuous and this extreme

amount of exertion could give a person a heart attack. I could barely move my boat. It was everyman for himself, a dead heat

battle. I knew that the only suitably sized landing

point in a geologically stable area was south five miles away. However on our previous passage running up the

east side of this cape I had noted that there was a tiny but useable in an

emergency landing area beneath very unstable traprock cliffs at a waterfall

midway. Anything in an emergency would be better than nothing, I thought. Later upon consulting with a meteorologist at

Pond Inlet, Hermann Steltner, he said that katabatic wind actually not only

blows the water flat but actually depresses the water in this particular

area. Now I knew I was not imagining

things. The picture below is of the general area in Pond

Inlet showing some of the igneous geology. |

|

03 |

|

I was told that the Penny Ice Cap south of the

town, Pond Inlet can generate severe katabatic winds which will blow kayaks

away from shore and can tip them over.

This area looks very innocent in the picture below but on a warm

summer afternoon without any warning this type of wind can develop. The safest solution in this area is to

paddle close to shore in the lee out of the wind shadow. The Penny Ice Cap is on the right to the center

of the horizon and This area is impossible to forecast trends only

hourly readings on a barometer, instead Hermann Steltner, meteorologist in

Pond Inlet told me that a barometer has to be read every few minutes over a

half an hour to deduce a trend.

Extremely low numbers can be generated by just the atmospheric

pressure from an ice cap such as the |

|

04 |

|

I paddled my kayak in To be doubly sure of what I would come across as

a kayak paddler, when I arrived at Arctic Bay we sat down and start discuss

what kayak paddling conditions I might expect to encounter now that I was

there. Big question on my mind was what would the ice

do? As I looked out the window while

flying in from what I saw from the air there was ice everywhere. This happened to be a year for heavy annual

ice. He said that annual ice is unpredictable. It will drift into a bay on the tide and

sometime later will drift back out again.

When this happens boaters become trapped where ever they might be and

it is called “drying out”. Only

someone like Glenn with his ultra light aircraft has any mobility to escape

this type of entrapment. I had no

experience with annual ice. Below is a

picture of annual ice that had drifted in behind me as I paddled down Adams

Sound – I got to dry out a couple days. |

|

05 |

|

Below is a photo of that annual ice which

stacked itself on the shore 50 feet away from my tent. The ice stacked itself soundlessly over

night. The next morning I was shocked

to see this stack and was very glad that I did not happen to put my tent in

that spot. It was just a tiny spot

with an eddy that brought the ice up on shore. |

|

06 |

|

Glen Williams described to me an intense

windstorm of 70 knots that occurred just a week earlier on an innocent

looking, blue-sky afternoon. The storm did a lot of damage all over town by

picking up and smashing all sorts of objects like lumber and including his

ultra light aircraft. Winds of this intensity had come completely

unexpectedly so things even though they were tied down hadn’t been tied down

well enough to withstand this wind of 70 knots. He advised me that these windstorms could not be

predicted and at the airport in Nanisivik that particular windstorm was only

blowing at 30 to 40 knots, but down in |

|

07 |

|

I had been told that if Adams Sound looked dark

and threatening when viewed from When paddling a kayak it is hard to judge the

size of waves when they are being blown away from you. I discovered this as I was leaving As I made my way down out of the bay just within

less than a mile from town the speed of the wind dramatically began

escalating every each few feet. It was one of those situations where I told

myself, “you better be in control of your kayak and ready to dive into shore

once you see a place where you can land when you get out to the point”. I had already camped there so I knew where to

pull in that was easy to bring my kayak up above the tide line on the shore. By the time I blew madly along to the point near

Society Cliffs just two miles away I was experiencing waterskiing conditions

only nobody was towing my kayak and to stay upright I had to lean over toward

the wind. I used a most extreme low brace such that I

leaned over the side onto my elbow which was on my paddle blade. I could automatically feel my need to

counterbalance the thrust of the wind by reducing my body surface area

presented to the wind and out boarding my center of gravity to the point

where I was countering the roll over effect on my kayak from the wind, in

other words I leaned out and down until I could feel my kayak was in neutral buoyancy

to the wind to keep my kayak upright. Another situation I came out from a point and

started to paddle through a tiny opening into a little harbor flanked by

shallow shores near Just as I without the least suspicion edged my

kayak into the opening near I felt as though I had just gotten myself behind

a jet on take off. Instantly I was in an impossible situation where

I could not paddle against this wind and worse yet I had to really not be

afraid to hunker down over my deck to lower my center of gravity. Immediately without any thought of indecision I

applied the full strength of my rudder to get out of the wind and used my

body as a sail while I was heading down wind.

I was glad that I just happened to have been

paddling with the full surface area of the “barn door rudder” in the water at

this time because often in low wind conditions I would use the most minimal

surface area of the rudder to control the bow. Who would have thought! It all looked so innocent. The sky was blue with no clouds the sun was

out nice and bright there was no scud hurrying by overhead. Below is a photo, taken from the town, The area I camped at after having been blown out

of the bay was on the point to the right of this picture only two miles

downwind. |

|

08 |

|

In Upernavik Greenland as I was paddling my

kayak as close as possible to the base of the mountain Sanderson’s Hope I

have had the experience katabatic winds.

These down drafts were coming off the top of Sanderson’s Hope on a hot

summer day. All the while as I was

struggling to maintain myself I looked up to see gulls flying next to the

rocks completely unaffected. Even though I was as close to the cliffs as

possible hoping to be out of the downdraft my strategy did not work. In such a threatening situation the worst

thing to happen is for me to loose my paddle, so I tied my paddle off to my

deck line, just in case. This mountain, Sanderson’s Hope rises straight

out of the water to an altitude above 3,450 feet. It is the only mountain in the world that

is like this. Below is a photo to illustrate wind patterns on

the water. Where the water is flat

there is no wind and This picture below illustrates wind shadow on

the water. The picture happens to be

taken in the Upernavik area showing Sanderson’s hope the tallest pyramid

shaped mountain on the left horizon. I

was approaching Sortehulle at a very oblique angle from its south side I was

east of it in my kayak. I had just emerged from Torssukatak passage,

famous for its waterfalls that come out of the sky, and was between Nutarmiut

and |

|

09 |

|

Sortehulle / Akornat is

a straight up and down cliff area on both sides where many sea birds

nest. You can see the extensive white

area on the rocks which is the bird droppings accumulation. This picture below is a more typical view of Sortehulle,

which I took from my kayak with a broadside wind of 10 to 12 knots. As a kayak paddler I am not comfortable

paddling through this passage because there are too many miles to go with no

place to land, just straight up and down cliffs. |

|

10 |

|

Just to confirm my observation while I was in

Upernavik I talked with a motor boater who said Sanderson’s Hope and Torssut

Passage are dangerous places where a motorboat can be flipped over by down

drafting katabatic winds. Katabatic

winds are especially apt to occur on a cheery summer day without a cloud in

the sky. Below is a photo of the opening to Torssut that

shows the sheer basalt cliffs dropping 3000 feet into the water. |

|

11 |

|

As far as barometric pressure change is

concerned I learned from experience to watch the clouds. I have seen clouds come in and turn into a

storm while the barometric pressure showed no change for an hour. Below are three photos that show exactly my

several experiences in Torssut passage when a wind storm came. This experience arrival of a windstorm while I

was on the water my first time happened with such sudden intensity. I was paying attention to the readings on

my barometric watch which were unchanged.

I did not notice that clouds were rushing toward me down the valley

between Umiasuqssuk/Umiaq Mountain and I wasted no time deciding what to do. Using my best emergency tactic I tied my

paddle off to my deck line to my kayak so that should the worst imaginable

happen I would not lose my most

important tools, my kayak and my paddle. I accessed the situation and headed for the

nearest shore where landing was possible.

I dot out dragged my boat floating it on the incoming waves up onto

dry land, tied it off with extra lines to the rocks. I found a fairly level spot and set up

camp. Later I was unable to stand up in the wind as I

attempted to get some water and rooster tails shot up from the waves that

crashed into the rocks where my kayak was tied on dry land. Even though I had been monitoring my barometric

watch no change showed until an hour after the storm hit. The storm had arrived unabated from the

open water of Below is a photograph of this area just as a

storm is beginning. Note the dense

clouds to the right side of the photo.

The clouds and wind are just starting to tumble down to the water. I was not in my kayak when I took these pictures

but I knew from previous experience that this was indeed another one of those

storms I had already experienced in this area when I was paddling here. |

|

11

Start up 40 kts Torssut |

|

12 40

kts blowing through Torssut |

|

14

Upv 40 knots coming at me |

|

I have learned the value of knowing topographic

effects on storms not just simple topography such as a mountain a passage or

a sound but the effect the ice cap in an area can have on winds. Below are some pictures illustrating

topographic temperature – air density of cold air effect on a warm air storm

coming across I have experienced cold air pushing me down

inside Laksefjord / Eqalugarssuit that was displacing the less dense warm

air. Below in the photograph warm air

from the west is being held back at water level by cold dense air from the

Greenland Icecap to the east or left side of the picture. This was a temporary situation that was

over come by the power of the storm coming in from the right side or

west. In the picture I am looking

south from the I was not in my kayak when I took this picture

and notice all the icebergs to the left.

These icebergs were blown in by the wind from the north from a storm a day or two

earlier. Living in Kullorsuaq we were constantly having to think about icebergs being blown

into the bay clogging shipping access to the town wharf. |

|

14 Kullorsuaq storm coming between |

|

As a paddler I pay special attention to not only

what the clouds are doing on the water but I take into consideration the

effect topography and air pressure systems can have on paddling conditions. Gail

Ferris gaileferris@hotmail.com |