Excursion in Sea Kayaking at Barrow

|

Gail E. Ferris

|

|

1991 there I was gazing

out of the airplane window and it was my first time flying north from |

|

Alaskan Glacier on the way to Barrow 001 |

|

We flew over the last

mountain range, |

|

Brooks Range just before coming to the 002

Cloud cover on the way to Barrow 003 |

|

As we descended into

Barrow on a grey August day, Then came the weather

report over the plane's intercom system, with determined resolution I

listened as the voice reported in decidedly ominous tones that the winds were

from the west at 18 to 25 knots with higher gusts and the temperature was

45. Immediately I recognized by the

intonation that the implication was that a strong low pressure system was

about to produce some nasty stormy conditions, which I would have to wait to

pass before I could venture on the water in my kayak. |

|

Patience was as aspect,

which one acquires from travel experience.

I had just returned from my first experience of traveling in a truly

foreign country, which was Once inside the airport

terminal a kindly Inupiat lady, Edith Wilson, rushed up to me and asked if I

were the party whom she was to be meeting.

I told her who I was and she immediately loaned me change to use in

the telephone. This was my first

experience with the native people of Barrow and there were many more, just as

wonderful, to come. |

|

The cab arrived driven

by a young, perpetually cheerful native fellow who felt as obligated as I

felt guilty that he should load my ponderous luggage while I speedily piled

into the cab as many pieces as I could and he handled the rest. Then I dropped the news

that we were going elsewhere in town, where I had a vague idea, to pick up my

Klepper, which was just two more bags, which weighed more than I wish to

remember but their contents were essential.

As the weather blew in, I was soon going to find out how critically

essential each piece of equipment was to be.

With a pretended air of

aplomb I asked the cabby to drive me to some place near the water with some

grass where I could camp and launch my boat from. As we passed by a street, which led to the

water, the hack said that he could take me to a hunting site for ducks where

people camp, which was near the water.

After a seemingly long, long drive over the dirt streets we began to

emerge from town heading out along the dark sand beach, which I could see,

was narrowing to a peninsula. I could

feel myself becoming more and more excited as there before me I could see

that, yes indeed, we were driving out on Point Barrow and there on one side

was the exhilarating sight and sound of the waves of the Chukchi Sea coming

into shore and on the other side the Beaufort Sea, but to crown it all at the

end was the great mysterious Arctic Ocean.

The dutiful, patient

cabby dropped me beside a lush mound of sand dune grass, which is slightly

coarse and sharp but much better for camping on than sand. Excitedly I generously paid him a tidy sum

and profusely thanked him, for little did he know how priceless his patience

and diligence were to me, because my disability makes me incapable of moving

my equipment any distance over land. So now comes the fun I

say to myself. First order of business

is to introduce myself to the people who are staying in their summer cottages

here. Spotting an occupied cabin I

knock on the door and I am invited in.

I open the door and find that this house is filled with the happiest

adults and the floor covered with the happiest children imaginable. I describe what I am planning to do

carefully reassuring them that I will be on my way once the winds from the

storm calm down. They tell me that

they do not mind my camping there. |

|

Bubbling with great

excitement I tell them of my previous Arctic trips and how much I like to eat

seal and that I would like so much once again to eat some seal. I ask "Could I buy some seal?"

and they reply "Well we are having some seal tonight for supper, would

you like to come?" I shyly

accepted not wanting to be a burden, but as it turns out this house is the

place where children come to play and people share whatever they have in the

true Inuit fashion. This moment was a

long ago imagined dream, which had now come true; there I was able to be

among the Inuit and to eat some of their native food. I was glad that on this trip that I was

indeed by myself, because I wanted to visit the I politely excused

myself after some tea and extracted myself from their cabin, which required

some strength to push open the door against what was now becoming a 25 to 30

knot wind. I knew that in just a

moment the wind could grab the door and fold it back making it very difficult

to bring around and close again. Once back at my

conflagration of gear piled on the grass I had to attend to the serious

business of finding and erecting my tent without accidentally having the tent

become ripped or damaged, or anything blow away in this bullying wind. I found the tent without much searching and

then the thought came to mind, did I pack my usual tent stakes the

"U" shaped 1/8 inch diameter aluminum ones? Or did I happen to assume that I could

easily find a suitable substitute here in the |

|

I would not be able to

tie my tent down with mounds of sand on the flaps. The wind will blow the sand away in

moments. This tent has to be anchored

with stakes and weighted with the rest of your equipment or else it will blow

away." I tell myself. I ask myself whoever heard of a place where not

only do they have no trees but not only that they have no rocks but the wind

blows like its going out of style! I'm glad my tent has the

orange rip stop liner, which I made last winter just for cold conditions like

this. I must be very careful to be

sure that the pole is exactly in the center where the reinforcement is

located when I start to erect the tent, otherwise the pressure of the wind

will cause the pole to puncture the tent wall. This photo is taken

again not in Barrow but in Upernavik Greenland |

|

004 |

|

Well I successfully

erect the tent but the wind is expected to increase, which inspires me to

question why do they sell airplane tickets to this destination they should

only sell tickets to nice places where the wind is somber and the

temperatures like August not January, where did I get the idea to come to

this place? The reason for my

choosing the Barrow area was because of its remote northern position, the

Inupiat population, the small size of the town and its drier climate than the

Seward area, which has plenty of rain and storms. This is more suitable for sea kayaking and

the only problems might be the ice conditions and possible polar bear

population, which I expect would be found along this coast. However the next time I look at the map and

say to myself that I think I would like to go there just because it is on the

map I think I had better remember this moment but on the other hand this is

part of travel and one cannot always expect to know everything about an area

until they learn how to access for themselves the available information. I had been informed that the winds in this

area in August averaged fifteen knots and blew from the east. What I had not contemplated is the

occasional meteorological excursions for, which this area might be known,

which could occur at any time. With

this in mind I pulled out my sleeping bag, crawled in and dozed off because

there was no point in worrying about what I could not control. |

|

Some moments later I

heard the exuberant voices of children happily engaged in play outside my

tent. Then there was a little voice

outside my door saying "Gail, are you awake here are some doughnuts for

you." And with that I answered

yes when suddenly to my surprise a bag of hot doughnuts are tucked through

the bottom of my tent door for me to eat.

I realized that it was going to be heard to starve in this

neighborhood. I opened my tent door

and told my beaming new friends outside that I would come by shortly to spend

some more time with them after I finished resting, which would be just a

short while. I was adjusting to the

change in time zones from where I had just spent three weeks in Russia so I

found that when it was convenient to nap, but after a few more moments I felt

like rousting myself to put on warmer windproof clothing so that I could walk

the beach and see how the approaching storm was progressing and visit my new

friends. I was interested in seeing

how these people relate to weather conditions, which would keep most people

in my area indoors. Extricating myself from

my tent was no problem but walking against the wind was challenging. I looked slightly like a humanized leaning |

|

I knew well enough not

to head down wind because I would find a stiff challenge making my way back

against the wind. I put aside

pessimism and decided that this storm would come and go and that my Klepper would

have survived shipping so that soon enough I would be assembling my Klepper

and be getting on the water, but now I would divert my attention to some

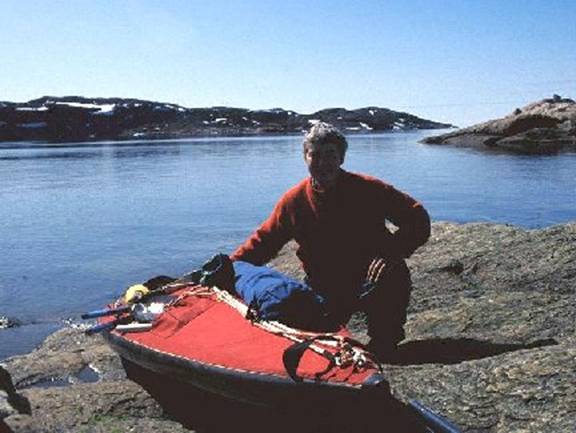

other things, which most likely be just as interesting. The photo is taken in Upernavik Greenland but it is

of myself and my Klepper Aerius I. |

|

Gail Ferris 005 |

|

I noticed as I slogged

my way up the beach that the waves were not as high as they should be in

proportion to the strength of the wind.

I recalled the remark that the ice was out far enough that it could

not be seen but that it never is really that far off shore when it goes out

in this area and that a powerful storm can bring the ice back in. I had the feeling that we would soon be

seeing the wind driven ice packs back in on the Chukchi side of Point

Barrow. I was glad that I had

anticipated this problem and had available the east side of Point Barrow,

which was protected by barrier islands.

|

|

Umiaq of Barrow covered with

seal skins 006 |

|

On the beach there was

an inverted umiak, which had a new skin covering and some paddles lying next

to it. The white skin was made from

six hooded seal hides, which had been meticulously prepared and sewn on by

six of the older Inupiat ladies of the area.

The younger women have to be taught when it is considered the time for

them to learn how to sew these skins by the older ladies who know this sewing

technique for blind stitching. The

sewing has to be done in synchrony so as to evenly stretch the skin over the

umiak frame in three dimensions. In

the world of the Inuit respect for tradition and survival go hand in hand

because the umiak is the most suitable boat to use for whale hunting in

Barrow by the Inupiat because the umiak can best withstand collisions with

the omnipresent ice floes. |

|

interior of umiaq on the beach at Barrow 007 |

|

The structure of the

umiak is designed to act as a shock absorber starting with the widely spaced

frame with a strong keelson, which has ribs that are attached to the

stringers by single point attachment and the skin covering is sewn together

in one piece over the frame and gunwale attached only to the inner frame

longitudinal with coarse lacing. The umiak is light

enough to be picked up and placed on an ice floe. With ecstasy I looked at every inch of the

umiak admiring its fine double blind stitched seams, which is waterproof

requiring that no stitch completely penetrate the hide but still be strong

enough to hold the hides together. I

crawled beneath the umiak to look at the frame and hoped for a bright calm

day when I could take pictures and video shots for myself to share with

others at home. |

|

008 |

|

I decided that it was

time to visit to happy cottage of my friends, Roy and Flossie Nageak, for

dinner. I couldn't think of anything

to bring as a gift at that time but I knew that at a later time I probably

could find something suitable. At

least I knew that we would have a wonderful time together telling stories

about our different experiences and laughing together as the children romped

about. I arrived and there was

Lucy one of their cousins watching the children and making those delicious

doughnuts while Flossie and Roy were away in town. I had a wonderful time watching just how

those doughnuts were made although I was really only watching the cooking

portion of the recipe. Flossie and Roy

arrived and out came the dinner. First

there was dried harbor seal in seal oil, then there were chunks of harbor

seal and lastly there was hooded seal boiled.

Everything was very good eating and we ate until we were full, which

didn't take long because seal meat with its oil is very filling and very

warming because of its energy and iron content. With the expected cold windy night I was

most thankful that I could be eating this meal because this is some of the

best food to eat. With the food, which

I had brought I had to bring a pound of butter to supply sufficient fat in my

diet. We discussed and

compared our perceptions of being on the water, interacting with others who

are native and non-native people and living in the |

|

Despite the howling wind

outside I began to feel that I was starting to doze off so I decided I had

better leave and politely excused myself.

Trying to look like I dealt with wind like this every day in

Connecticut I calculated my egress without inadvertently causing damage to

the door by accidentally breaking part of it as I forced it open against the

now forty mile an hour and more wind or by springing its hinges should I

either loose my grip on it or find my body being flung out with the door as

it is violently flung wide open as I hoped for the best. With luck I experienced none of the above

and I was glad that this simple tent was only barrier between the warm

sanctuary and the bitter wind had not been breached. Earlier one of the

children had had the experience of going for an unexpected ride on the door

handle, luckily without injury. As I made my way back to

the tent, not exactly with the stride of a fashion model, I realized that in

the interest of preservation I had better thoroughly tie everything down and

doubly secure the tent. This is one of

those moments when you are glad you went to the trouble of bringing a fifty foot

polypropylene white water rescue throw line because this item is well worth

its weight and size. As I came around the

corner I noticed that the cottage nearest my tent was now occupied. I waved hello to the children and while I

was tying down my gear they came over and told me that I should come over and

visit their house. Not wanting to pass

up another wonderful opportunity to visit and to be sure that these people

did not mind my presence near their home, I knocked on their door. Once again people who had not the slightest

idea who I might be or why I might be there invited me in, just as if we had

been friends for ages. Children and

grandchildren of all ages were having a wonderful time tea or coffee was served

and we sat in the bright kitchen absorbing the heat from the hot wood stove,

chatting and watching to see that the little ones were having with each

other. Sheldon asked me if I would

like a barricade set up around my tent to ward off the wind and while we were

busy talking Sheldon drove his truck next to my tent and put sheets of

plywood up to shield my tent from the expected winds of fifty miles an

hour. Although I thought that I should

experience this wind unsheltered to access the capability of the tent

structure and design I realized that if I wanted to sleep at all that night

that Sheldon's barricade was a good idea.

I never heard wind that

just screamed in the wires above. |

|

The Chouinard Mega-Mid tent with orange ripstop

liner 009 |

|

I left the warmth and

hospitality of Sheldon and Lucy's cottage for a charming evening in my tent,

which can only be described as similar to being inside a drum and bombarded

with screeching intermittently, absolutely romantic just like New York during

a riot combined with garbage collection all night. Nothing really mattered, I had no schedule

to meet but I would have preferred something else. All night it was grey

because the sun never set, which was convenient if I wanted to get up and

check anything but I was glad I had a twenty four hour watch because it was

difficult to know, which part of the day it was since all looked the

same. I like Arctic summer days, which

in Barrow were still without sunset on August 6th. The next morning I

crawled out to meet a somewhat slackened wind and to be confronted by a

profusion of ice floes, which had been just visible by binoculars on the

horizon but now had made their way on the wind to the west facing |

|

cold foggy morning on point barrow 010 |

|

I decided to move my

tent to a protected grassy zone behind another cottage after I cooked and ate

my usual breakfast and drank a cup of my espresso. On the previous day I

had obtained two gallons of water from my new friends. There was no fresh water available on the

point because the soil was sand. I had no idea how

serious it was to be out on this point with no available water all water was

brought from town in large containers by each family to their own cottage. I was advised to take as

much as I might need for several days because there was little potable water

on tundra. Was I surprised at this

situation and luckily I had brought my waterbags with me among my camping

gear. One should never be without

water. |

|

011 |

|

Although the topographic

map indicated numerous ponds much of this was poor quality, stagnant, saline

or surrounded with mud, which had the characteristics of quicksand. I began to wonder what other charming

natural phenomena might be awaiting me on my tundra vacation. On my two previous Arctic trips water was

the least of my problems. I was glad

that I happened to have brought a water storage bag and some cloth to strain

out the swimmers with. That same piece

of cloth, part of a camp towel, was used for every imaginable possible towel

application including bailing and washing out the kayak. Next order of business

was at long last to assemble my kayak.

All the pieces appeared to have survived UPS shipping undamaged, but

the true test was to come when they were to be assembled. Piece by piece all went together without

any problem. Now, I knew that once

again I could be on the water in the |

|

Klepper deck arrangement in 012 |

|

Today I would have to

wait and hope that tomorrow the wind will have decreased enough for me to

start my trip, because today the wind was still blowing in the thirty knot

range and I spent the morning relocating camp and assembling the boat. I visited my new friends

for a few hours and watched the Sabine gulls and a few Ivory gulls soaring

over the breaking surf looking for smelt.

Smelt were expected to arrive at these beaches in great schools, which

the native people dip and catch in several types of small nets. Smelt are a type of capelin are tasty when

fried but you have to eat many of them to feel full. On the inside of the

point Sheldon and some others were fishing with shallow gill nets anchored on

shore and about one hundred feet off shore.

He was finding that he was catching so many whitefish that he had to

empty the net every evening. These

whitefish, which are excellent eating, he was storing frozen for his family

to enjoy throughout the year. The next morning the

wind had lessened to fifteen to twenty knots and the cloud cover was breaking

up. I had breakfast, broke camp and

went through the ritual of hauling the boat and all my gear to the water's

edge on the east side of Point Barrow directly across from |

|

As I was packing my

kayak and donning my vinyl dry suit the wind began to increase slightly. I realized that I must find my routine

winter paddling windproof hat, scarf and the mittens I wasn't sure if I had

packed. With greatest relief I found

these now critically necessary items, which I realized that I could not

paddle in the conditions of this area without. During breakfast I had the impression that

the temperature might be close to freezing until this impression was

definitely confirmed as I noticed that ice crystals were in my breakfast

cooking water. Thoughts came to mind

about how easy it can be to make a fatal mistake in this area, where not only

is it cold but the wind blows strongly as well. |

|

Gail Ferris in Rukka vinyl drysuit in 013 |

|

My new friend, Mae,

watched me as I struggled to quickly load my kayak before both she and I

became too cold. Mae sat aboard her

all terrain three-wheeler and I felt sorry for her because she wanted to see

me off but the wind was making us more and more miserable. Finally, I jammed in the last few pieces

and lashed down the solar panel for recharging my Cam-Corder batteries onto

the deck and at long last stuffed myself into the cockpit. With the wind now threatening to blow me

broadside off shore I eagerly waved good-bye to Mae and she headed for the

warmth of her cottage while I summoned my paddling muscles and skills to

force the kayak back closer to shore.

I decided that I would cruise along the shore heading south and cut

across to the opposite bank when I felt that I had seen enough of the

easterly shore of Point Barrow. As I

was heading for the mouth of an inlet just north of Imipuk lake I recalled

that there was a helicopter airport on the shore of that inlet. I decided that since my best means to get

there would be to paddle rather than walk that now was the time to visit this

airfield where I could very likely obtain the best weather information. Although I had brought my FM NOAA weather

radio, NOAA does not broadcast on those FM frequencies in the Barrow area;

instead they provide up to date weather information on local AM radio. |

|

Paddling was very

shallow in the estuary, but I knew that the Even though I did not

know the weather forecast, I decided that it was more important to take a

chance than not to know what the weather was expected to be doing for the

next several days. Next thing I knew my concern

began to rise as I noticed that I was paddling into increasingly stronger

gusts of wind and that snow was beginning to fly. My face began to feel

colder and colder as the clumps of snow plastered themselves onto my

skin. I hunkered down, tightened my

scarf around my hat and pressed forward with all my might finding that there

were moments when it was all I could do to make any forward progress at all

despite my summoning not only my arms, shoulders and back but my legs as well

using the paddling technique called lifted knee. All too well I know that

when the wind speed is in the range of twenty five knots that I become barely

able to make much forward progress with a kayak, however there is some

advantage to paddling a fully loaded kayak in that you have some momentum to

assist once you get the kayak moving.

This is one of those moments when I am glad that I have good stout

paddles. There is no compromise good

equipment unless you need an excuse to stay home. I just hunkered down to

make myself as small a target for the wind as possible. Then I began to really use my staunchest

stroke which comes from my lower back.

I push on the top as I pivot from side to side hardly bending my arms

at all. I lean my body weight on my

paddle. At long last I arrived

at the airfield but the relentless wind and snow was beginning to make me

feel cold. I moored the kayak and

trudged up the bank searching for the most likely place where I would find

someone such as a pilot who could answer my questions about the weather. After some walking I found a helicopter,

which was being outfitted. The

personnel were of as much assistance as they felt necessary and without

wasting time I headed for an actively occupied building searching out the

office area. Once within the building

I doffed my hat and scarf and stepped into the offices. Questioning another pilot brought similar

results such that I bristled and passed a remark that suggested better

information must be available than what I had just been given. Another fellow, sensing that perhaps he

could offer assistance, dialed the weather bureau in Barrow and allowed me to

talk directly with Bill Spencer the NOAA forecaster. Discussing the expected pattern of lows and

highs with Bill he told me that from his information there was unlikely for

the next several days to be another low pressure system passing through. At present he told me that we were still

experiencing and could expect to experience decreasing westerly winds from the

low, which was just passing through and that the temperatures could be

expected to remain in the thirties to low forties. With this information I now knew that I

could reasonably expect to go on my paddling adventure and most likely be

able to make it back for my flight home.

|

|

Now greatly relieved I

thanked the fellow who had so kindly permitted me to talk on his telephone

and walked back to my kayak self assured that once again I could experience

the Arctic, only this time I would be completely alone for a number of days,

not just one or two. Gingerly tucking myself

back into the cockpit I launched while the westerly wind blew me madly along

almost ramming and miring me in the shallows of the easterly shore. The combination of a good following wind

and an elevated center of gravity made the Klepper feel much less stable than

when heading into the wind. I my hurry

to leave I had carelessly packed too many items into the cockpit area making

my seat feel somewhat like a rather jiggly throne. I slightly imagined myself as Queen So and

So and wondered what it would be like to rule the world from my red

kayak. Such ridiculous thoughts were

banished as I found that I was perilously close to grounding out in the

shallows again. I realized that I had

better pay strict attention to where I was going or the mobility of my throne

would be most deleteriously affected. I was headed out

northward and around the perimeter of the inlet then onward out to I decided that this was

my long awaited opportunity to study in detail this area because animals

during previous short solitary moments in the |

|

Long Tailed Jaeger 014 |

|

I was looking forward to

the possibility that I might see and capture on film the delightful and

hilariously curious Arctic fox. I knew

that despite the likelihood that the appearance of a fox would be unexpected,

this would be not be a problem. With

slow movements I could very likely get out my camera equipment from where

ever it might be and take pictures and video shots without scaring the fox

away. The fifteen knot wind to

my stern was pushing me along at a speed, which allowed me to observe the

banks for anything interesting.

Although there were no rocks in this Quaternary Gubik Formation there

were soil horizons, which had been produced during different geological

epochs by different conditions perfectly preserved by the cold of this area

such that there were included ice lenses.

These ice lenses, which I could see were between one and two feet

thick. What really caught my

eye aside from the ice lens which was hard to believe was this unbelievable

deep brown humus laden soil. The soil

was deposited during a much warmer time. They in some areas near

Barrow have been found to contain wooly mammoth remains. At this time they are in the process of

melting causing the one-foot thick layer of peaty turf, which is the upper

most soil horizon to slump over the exposed bank along the water's edge. I wondered to myself what might be still

trapped in those ice lenses and at the time I did not think to take a sample

and melt it for observation and possibly see how it might taste. These ice lenses had no particular color

other than dull white. Below this was

a horizon of clay, which most likely was a marine deposit made when the land

mass was either lower or the sea level was a few feet higher. I was just fascinated to

think that such a deposit of soil that remains from an entirely different

climate. I thought about my

experiences in |

|

Gubik Formation melting ice lens trapped in

tundra 015 |

|

I noticed that I was

beginning to feel chilled by the following wind and my lack of need to expend

energy for paddling, so I decided that since I had very likely covered enough

distance I might as well put into shore.

My first priority for a landing area was one, which had a ravine,

because the ravine would be very convenient to bring the kayak up into,

rather than have to pull it up the steep bank. I wanted to avoid any possible risk of damaging

or worse yet, loosing my Klepper. These ravines were the

result of where an ice wedge had formed and now had melted leaving a slumped

frost scar. Frost creates the minor relief

features in this flat coastal zone.

The ravine was a narrow, three to four foot deep depression without

any specialized plants, which would eventually become established in its

protection because it had slumped quite recently and its soil had not yet

changed because there was no run-off of nutrient rich silt accumulation in

it. |

|

As I unloaded my kayak

and heisted it up into the ravine. As

the usual forget about rocks, there were no rocks to tie off to so I

improvised with some wood pieces I found. I had been hoping that I

might find some water in it. After the

closest inspection, which means I very nearly stood on my head, I found in

this ravine that not only was there no water but that were no plants, which occur

on the edges of wet areas. I was looking

for specimens of liverworts and specialized mosses to collect just out of

curiosity. Ho hum, I thought as I

went about the mundane activity of erecting the tent. This only took a couple minutes. This area had good ground for tent pegs and

plenty of soft tundra grasses. Once

the pegs were in the ground solidly, the single pole in the center went into

place, in just moments. I tossed in

all the necessary gear and crawled in.

Once I was within my double walled tent immediately I felt much warmer

from just the effect of being out of the wind within the sanctuary of my

tent. This once again brought to my

mind how great the importance of suitable equipment is and how careful one

has to be in the |

|

tent showing space blanket, Thermarest pad snow

border and ripstop nylon liner 016 |

|

I busied myself with

laying out the ground cloth, which was an aluminized "survival

blanket," and inflated the "Thermarest" pad. My sleeping bag was a combination of items,

which were meant to serve more than one purpose just in case something

unexpected happened. The outer layer

of the sleeping bag was a "Gore-Tex" non-rigid bivouac bag designed

to expel condensation and repel liquid water.

The next layer was a very light weight soft feeling "Thermolite"

filled sleeping bag for bicyclists, which only weighed thirty six ounces. My next layer was quilted "Thinsulate"

underwear to, which I had added a polyester shell, storm flaps and a onto the

jacket two-way zipper for increased wind protection and ventilation. On my head I wore a "Gore-Tex"

trooper hat lined with down and sheepskin over, which I wore a "polar

fleece" balaclava hood because I knew that the head is the area, which

loses the most body heat. I never took

that trooper hat off during my entire trip and it has served me well many a

time for the last twenty-five years, however if I had to replace it I would

buy one with insulation that functioned even when wet. You may wonder why I

choose this particular combination.

The reason was that I wanted something, which I could not only walk

around in, which could also be combined with something to sleep in. I wanted to be comfortable when I was

sitting up cooking that would not leak cold air. The inner layers of

underwear, which I wore beneath my drysuit, were two layers of light weight

polyethylene "Thermax" and a rag wool sweater. My socks were also "Thermax" in

layers. I slipped out of my drysuit

and into my quilted layer topped off with my hooded "Gore-Tex"

parka and pants. I went out to go for a

walk and quietly explore the tundra, just to look, not to disturb. I wanted to know what plants grew there and

what animals were there. |

|

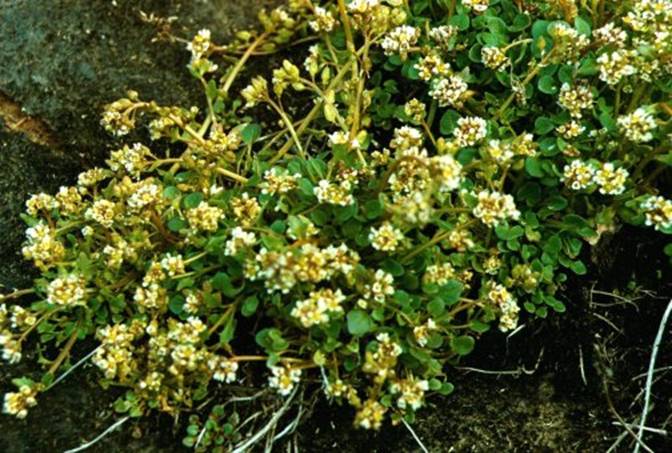

My most immediate note

was that these plants were not those, which I had seen on my other Arctic

trips. The dominant species were

different types of grasses and sedges, which grew in luxuriously, and

oppositely the lack of Vaccinium and other acid soil shrubs. The soil may have been more calcareous but

I did see some acid bog plants in wet peaty areas. |

|

everything is 6 – 8 inches tall 017 |

|

The color of the

grasses, which were only four to six inches high tussocks was yellow but

within each tussock were the green grass spears of this year's growth. The

retention of this old growth from year to year by these grasses is a

mechanism for protection against the harsh winds of this area. However the

grasses do loose their leaves when the cyclic lemming population has become

so numerous that in order to survive they become forced eat these yellowed

leaves during that particular year.

When the lemmings have eaten the yellowed grasses the tundra becomes

green. Now that I was ready to

go out exploring to see more of what plants grew there and to look for

water. Before I left the campsite I

started recharging another of my video camera batteries because the batteries

only need four to five hours of sunlight exposure to become recharged by my

solar panel. In these cold conditions

I bring four batteries because they cannot operate the video camera very long

but at least they can be recharged by the solar panel anywhere in the world

provided that sun light is available. The question of water

was rather vague, but I wanted to augment as much as possible my supply. As I made my way inland I found some

shallow ponds surrounded with matted aquatic mosses anchored in the layer

peat, which I decided would be not threatening but most likely be safe to

walk on where not only could I fill my buckets but my shoes as well, and

quite nicely at that. I had given up

caring about such trivia as dry feet long ago. The air temperatures were not

low enough to cause me discomfort. |

|

Ranuncula Buttercup 017 |

|

With two buckets of

black, murky water I returned to camp.

Compelled by my fear of running out of water, which I had decided

would be the most absurd reason to cut short my adventure. I was prepared to filter

the swimmers out, which looked most likely to be daphnia, aquatic plants, and

mud, which made the water nearly black with their dissolved tannins, etc.

with my truly all purpose piece of non-woven rayon called "camp

towel", which had served me most well during my previous weeks of travel

as a wash cloth, a towel, and had been planned to be used as a boat sponge

for bailing on this trip. So now it

was to serve another purpose because I really don't think it is quite exactly

inspiring to cook with complicated water.

After using my light blue towel for filtering this water it became

just about as black as coal and it was very difficult to scrub it even

slightly back to its original light blue.

I never knew just exactly how it tasted because I cooked with it and

with my espresso coffee I doubted that I would ever notice even the slightest

difference between vile and more vile.

On my return to the tent

I glanced over the bank to see if any water birds were about. Just in front of me only feet away were a

group of northern phalaropes just as busy as could be seeming to be skidding

around in little circles going one way and then another dabbing in the water

with their long little black beaks for some sort of aquatic delectables such

as little shrimp all the while completely ignoring my presence. They always stayed just a foot from the

water line where the depth must have been the best for capturing their little

prey, which were for some reason in these shallows perhaps because they too

were preying on some organism in this zone.

Very carefully, so as to

not loose this precious moment, I retrieved my cameras and with greatest care

not to frighten away these busy creatures, the phalaropes, I prepared my

cameras for taking pictures and approached the shore. I positioned myself comfortably so that I

could just wait motionlessly for their return. I was hardly breathing as I waited to see

how close they might come to me. I sat down on a rock

when low and behold there was no problem as far as they were concerned. I discovered that they were just about walking

over my feet. Next thing I knew they were

actually too close for focusing. I

couldn’t believe it, talk about friendly little birds these phalaropes are

the ultimate. And you can see in the

photo the phalarope spins around in shallow water just fast enough to bring

up zooplankton for them to gobble up from the sediments spiraling upward in

the column this bird has created. |

|

Phalarope 019 |

|

I found it quite true

that the best way to obtain pictures of animals is to wait until they come to

you. Now the classic

exception when you are on the water is if you happen to be next to a tern or

gull nest. Next thing you find is you

are getting bombarded and it is not a pleasant experience to say the least. Mixed in with the

phalaropes but at a distance of six to ten feet were dunlins and a Baird's

sandpiper. The dunlin had a very

striking black patch on its stomach and the Baird's sandpiper looked as usual

like a slightly squashed, spotted sandpiper.

Its uninterrupted moments like these, which make a trip worth it. In among all this

activity I spotted some Beroe, which are a type of small two inch diameter

comb jelly or ctenophore that feeds upon small zooplankton such as tiny

shrimp in the water. The water was

unfortunately too turbid for me to take a picture of these transparent,

iridescent, reddish pink speckled, almond shaped comb jellies, which spread

their mantle like a net to capture prey.

|

|

Beroe 020 |

|

I watched a pair of King

eider ducks come by but they immediately flew as soon as they recognized my

presence. They are elegant ducks and

the male is particularly colorful. After

the phalaropes had gone elsewhere I climbed back up the bank to look at other

things. When it comes to looking

at plants in this area one must not only get down on their knees but even lie

down to be at eye level or resort to standing on one's head to see what types

of plants are growing there. Plants

are so tiny that often the leaves are just barely a quarter of an inch long

and the entire plant one inch high.

The flower stalks can be higher such as three or four inches high but

then again the flowers although brilliantly colored are most often very

tiny. The largest plants that are easy

to notice are cotton grasses or Eriophorum species, which on each plant there

was a large nodding white plume about an inch in size and another plant with

large dark green shiny rounded spade shaped leaves two inches crowned with a

very thick flower stalk five to six inches high with several fluffy white

flowers called a petasites. The

petasites looked very much different than all the other plants of this area. Among the other plants

were in greatest variety six little tiny types of drabia, a member of the

mustard family, which are not particularly interesting to look at until I

stopped and thought about the many well known cultivated and weed varieties,

which grow in my garden at home. Some

of these plants, which are first to grow in the early spring are either the

same species as what I was seeing here or very close relatives. It is hard to imagine an ordinary mustard

plant with its intricate leaves can be related to these stubby, simple

looking, tiny plants, but this is what makes looking at plants in various

parts of the world most interesting. |

|

The most ethereal plant

with the thinnest imaginable stems was a member of that tenacious weed, the

chickweed or stellaria family. This

stellaria was hidden among the grasses having stems which appeared to be

about as thick as hair with whitish grey green very delicate lance shaped

leaves topped by tiny white flowers. On my way toward the

pond in marshy ground I found some pedicularis with lovely pink flowers. These plants seem to often grow in marshy

areas and although the small leaves are finely divided resembling ferns, the

flower on top of the stalk is always very spectacular and beautiful with each

bud slightly resembling the flowers of the pea family. I saw other plants in

the antennaria, anemone and saxifragia families, which all had the odd

looking, much simplified, rubbery, thick, tiny leaves that only from the

closest viewing could be identified.

Sometimes inverted binoculars have to be resorted to for seeing

details. This was the lilliputian

world of botany where one picks a bouquet of flowers with tweezers at best

and it is hard to imagine that these plants, which have specially adapted to

desiccating wind, long periods of darkness and cold have much larger

relatives elsewhere to the south. Just as I reluctantly

was about to duck into my tent a pomarine Jaeger came flying by. I had enough time, this time, to capture

its image with my video camera as it preformed its typical low level gliding,

flying and soaring all the while closely scrutinizing the tundra for

prey. The Jaeger paused its flight

momentarily to more closely observe the shallow ravine next to me, which had

some small sunken holes in it. This

was during the late afternoon, which in other areas of the The sun had to be

ignored, as here it does not set in early August, but the time had come to

come to prepare dinner. It was a

choice of some sort of dehydrated soup, dehydrated and freeze dried meat,

poultry and vegetable mixture with noodles or rice for carbohydrates and some

powdered fruit juice such as tang or spiced cider. I think that next time I will label my food

more completely. I found that not

knowing what I was preparing to eat before hand was not particularly

pleasing. |

|

022 |

|

For dinner preparation

the first order of business was to bring to a boil that previously mentioned

filtered, "complicated" water, then the ingredients are added and

cooking is continued as necessary. I

cook within the tent with my "Svea 123" out of the intensely cold

wind carefully adjusting the flame for safe and optimal heat production. I adjust the openings at edges of the

bottom in my floorless tent for ventilation as needed. Out of necessity I had learned how to cook

within a tent, just as one has to do when cooking in a boat, and the worst

imaginable thing to happen is a fire. Cooking is always a

progressive affair where lots of little pots of water are heated up and

things are cooked. I ate and cleaned up

then I rearranged my sleeping bag for warmth and comfort and settled in for

the night, but I was not sure what I would be greeted by in the morning as

far as precipitation was concerned because some snow flurries had been

blowing about shortly before I retired to my tent earlier. Being that I was alone and had suitable

clothing, plenty of water and food available I was not too concerned about

snow. I had no deadlines and my time

was my own but I certainly hoped that all the plants would not become covered

up by the snow. |

|

023 |

|

Today was the ninth of

August and there had been some light snow during the night. In this area precipitation often occurred

during the earlier hours of the morning and the weather would improve as the

day progressed. The changing angle of

the sun in the late afternoon would create visual phenomena and usher in weather

changes. The Inupiak word

"impac" was for the commonly seen mirages in this area, which are

caused by air temperature and solar angle, which makes things too distant to

be normally visible show on the horizon.

These mirages sort of build up, shimmer and die back in a short time

such as thirty minutes. As a boater I

was cautiously aware that I might be looking at something that may be a

mirage of this sort and that often the angle of the sun effects one's depth

and distance perspective. As a

precaution when I got on the water I stayed quite close to shore and

cautiously double checked the distances involved as compared to my position

on the chart so that I was sure of where I was and how wide each bay crossing

was. There have been some rather

amazing stories of ditches looking like huge holes to people and I myself

have seen rocks in the distance on other trips, which looked like large

boulders only to come upon them and find that they were ten inches in

diameter. I wanted to avoid making a

mid crossing discovery where I would be saying to myself "this crossing

is taking too long" because my eyes had been tricked by the magnifying

effects of refractory atmospheric conditions. |

|

024 |

|

So there I was squinting

at my 1:250,000 topographic map at the tiniest lines representing peninsulas

and dots for islands making my way down the coast heading east with some

helpful wind at my back. The waves

were very slight. Each estuary had one

major factor, which didn't at the time impress me, which was that they are

very shallow. The six inches of high

tide filled them during high tide but at low tide there is endless shallows

often just skimmed with water and as might be expected good old mud, not the

kind you walk on, but instead the kind, which walks on you. I tiptoed, so to speak,

past Ikpik Slough looking for the suggested peninsula that the chart showed

thinking to myself how much fun it must be to make a chart, which has to show

these details when the only difference between a sand bar and a peninsula is

a couple inches of elevation and maybe some clumps of low growing grass. Places such as where I live in Connecticut

where there are solid rocks and six foot tidal range and the accompanying

seaweeds make the coast line is very definite and even when I have been way

up in the salt marshes on a spring tide the saltwater line is well

defined. This ambiguous coast inside

the estuaries was a very amusing experience.

I proceeded on for

Tekegakrok Point and stopped near Just as I put ashore and

climbed up the bank a small light brown and mostly white hawk probably an

immature Northern Goshawk, which took to the air the moment I came into its

view. I was delighted to be able to

have had this experience and later I was once again visited by two Jaegers

and one of them was a Pomarine Jaeger in the light phase typical of Arctic

bird species, which had a distinctive trailing tail feathers, which looked

slightly like two spoons. The extended

trailing tails of Jaegers are one of the most distinguishing characteristics,

which immediately draws your eye to this precocious flier. I went through my usual

campsite routine and once again thanked those such as Chuck Sutherland and

Jon Cons who had introduced me to the concept of bringing along a light

weight stainless steel thermos for storage of hot liquids especially Knorr

dehydrated soups for those cold hungry moments. I ate my previously prepared lunch, which

had been stored hot in my thermos several hours ago when I cooked

breakfast. The thermos I stow easily

accessible with bungie cords attaching it to the stringers or in my side bags

in my Klepper cockpit for what might be a critical moment. |

|

The exploration for

water was more demanding than today's paddling had been because it was

located a long distance from the campsite.

I became quite concerned about the possibility of not relocating my

tent as I watched it shrink lower and lower until I could no longer see it as

I strode across the seemingly flat tundra toward the edge of a pond I could

just see further inland ahead of me.

Fearing disorientation I retreated to retrace my way in what I thought

was exactly the direction I had just come and as I apprehensively scanned the

horizon found that it took several more seemingly long moments of walking and

vigorous scanning before I finally saw my little tent. To further add to my ill ease the tent was

not where I had expected to see it. I

realized that what I had just done could have been a potential disaster. In the In this area things like

broken sticks and trampled grass to indicate foot passage are not

available. The grass had already been

completely trampled by this year's seasonal passage of caribou. The North Brooks caribou herd comes to the

grasslands on coast in this area to avoid the heavy insect infestations of

the southern inland grasslands on their annual calving migration. The trees here are as

prostrate as possible with tiny branches no larger than the smallest branches

on a white birch. These

"lilliputian" trees, which were willows, had leaves and catkins,

which were between half and one inch in size.

I imagine that the caribou must feed on some of them when they are in

the area |

|

Salix herbacea 025 |

|

Before I retired I

examined the sky for weather and clouds of particular note. To my surprise I saw something I had never

seen before in the sky. Some

altocumulus clouds were showing a mid air hail event, which is called virga.

This virga looked like splayed rays of silver and grey, which extended into a

weakly defined nimbocumulus layer of clouds.

I captured these clouds on film.

Another unusual event occurred previously as I was flying at about

30,000 feet into Barrow. This was

called a glory. A glory is the shadow

of the plane surrounded by a halo being reflected back to me by the spherical

water droplets in the cloud layer. I

saw two of these side by side at the same time. |

|

The winds, this evening

were disconcertingly calm for the first time, which heralded the end of the

low pressure weather system. At At I quickly extricated

myself from my sleeping bag and tent for this long awaited wonderful moment

with video and camera in hand. To my

dismay the recharged video batteries were on the stern of my kayak in the

ravine. Knowing that the Arctic fox is so curious that it would be unlikely

that it would run away, I carefully retrieved those necessary batteries. The background for the fox was so dark that

I questioned whether the film in the camera would capture this picture, but I

took the picture anyway. Luckily the

video batteries worked and I was able to record the sound and sight of this

little fox as he barked at me on the beach below. Then in an instant he ran off, bounding

across the tundra barking all the way.

He was gone, just as surely as he had come. |

|

025 |

|

The next morning I

stirred from my tent to examine the little empire of hoar frost, which had

festooned itself everywhere even on the narrowest blades of grass. |

|

|

|

The world of the tundra

was now a fairy tale of crystalline thorns of ice revealing the preceding

evening's movement of air and pattern of humidity solidification such that

each plant had a layer of frost deposited in the same direction. The pictures I took of this display were

fascinating. |

|

026 |

|

As I moved toward the

beach my attention became riveted on a few phalaropes, which were standing

just at the water's edge each with its head at rest on its wing but with its

eyes open all the while being asleep.

Then at the moment the bird from within its subconscious detected my

presence awoke the phalarope, positioned its head in an attentive posture and

proceeded to take sanctuary by going into the water and swimming further up

the beach. This was an interesting

experience for me because it was the first time I had witnessed this survival

mechanism in actual use. |

|

The hoar frost melted

and the wind arose from the fair weather direction, the east. I packed my kayak and was off with the wind

blowing in my face at about ten to fifteen knots. I took advantage of the shelter of the lee

shore of Tekegakrok Point by paddling within the protection of its six foot

high banks. As a paddler I feel that

there are enough times when I will have to push against a head wind without

unnecessarily doing that sort of drudgery.

Then there was that

inescapable moment when I knew I must round the point and face the

music. Rounding points on a chart

always looks like simple straight forward short work, but in reality is often

not the case as sooner or later my mind would be starting to tell me that

this passage seems to be taking a long time.

Periodically I evaluate my sea position and the conditions because

frequently rips develop during tidal changes off of points where there are

hidden reefs, which are part of the point and how much current might I be

bucking. Rounding points can test the

skills and judgment of a kayaker but are also be an intellectually

stimulating experience. I remembered the

experience I had in Pond Inlet when my progress ground to nearly a halt and

it seemed ages before I finally was able to round a point because the tide

and wind had turned to oppose me. Here at Tekegakrok Point

the current and wind were opposing me. Then my eye caught sight of something

just around the point on the windward side in the insidious shallows. There was a wooden wreck with some ribs with

large sharp spikes projecting up through the surf. I thought about how my tender kayak was,

how soft the muddy bottom was and how cold the water was. The critical evaluation of my capacity to

paddle safely in these conditions requires a degree of pragmatism, which can

only come for experience and candor. |

|

Looking at the seas,

which were one to two feet I knew that they were a product of fifteen knot

winds. I felt comfortable with myself

and my trusty kayak this morning in these conditions. I knew that I had a stretch of about two

nautical miles of this sort of exposed paddling and that the wind conditions

were stable. I kept a close eye on

maintaining enough sea room and used the rudder to maintain a positive bow

angle. Rudders are very practical for

maintaining quartering angle as the wind side slips the kayak while I apply

my strength in paddling forward with the wind pressure against the forward

quarter of the bow. I was heading 155

degrees true and the wind was blowing from about 120 to 100 degrees

true. As I was making my way

down the point I decided that I wanted to capture the character of the waves

on video because this brings a touch of the reality of what being on this

type of sea condition is like to the audience. It feels more secure to take pictures when

headed into the breaking waves than in following seas so I felt confident

that I could safely and quickly enough get out my video camera from its

waterproof bag, which was stowed in the roomy Klepper cockpit between my

legs, not drop it in the sea and put it safely away again before the wind

pushed my kayak broadside up onto the beach.

I had just enough time although there was a moment when I had to

paddle the kayak out from shore with the camera dangling from my neck,

because camera operation took longer than expected and I was closing in on

shore. Luckily from my

experience I had found that the hull of the Klepper is designed to have a

special type of heeling synchrony where just as a wave is about to jump into

the cockpit the Klepper rolls on its heeling moment away from the cresting

wave in seas of this size and type.

These seas had occasional variation such that within a series of waves

there would be a few larger ones here and there, which is typical and can be

estimated by enumerating how many small waves there are between the larger

ones. In the As I continued south at

about 155 degrees true I came to the estuary of the |

|

Now with my trusty,

multipurpose instrument, which was now functioning as my mechanical bottom

sampler and depth finder otherwise known as a paddle; so named because that

is this instrument's most frequent use, I paddled and scooped my way down

into the estuary. The wind was blowing

me so nicely that I had to expend little effort to move along except for when

I missed the channel and grounded out.

I couldn't see the channel because the black gooey mud and churned up

water made it invisible. I did not

consider what the advantage of having high tide and pushing wind might be in

the reverse situation as I skimmed along.

I choose a peninsula

with a convenient water depth and sloping shoreline well covered with grasses

for sliding the kayak up onto. Later

after I removed the campsite equipment I slide it up into the shelter of a

crevasse, well above the water line and moored it to firmly planted

stakes. This area was different

because it had a thinner top layer of peat, which was often absent in places. There were numerous flat sterile polygonal

frost heaved areas of gravel, which because of their constant state of

churning upheaval are sparsely colonized by a few adventurous grasses and

lichens making these chalky light colored soil polygonal areas were nearly

bare. The type of underlying surface

soil could be identified by the types of plants, which grew on it, which gave

this area a blotchy appearance. The unusually large size

and number of |

|

The flatness of this dry

area was punctuated with shallow V depressions resulting from melted ice

wedges. Facing eastward there were a

few unusually deep, four foot deep ravines of these melted ice wedges, which

had slumping undercut sides, which terminated at the edge of the

estuary. Along the east facing bank

there was extensive evidence of melting ice lenses with large sections of

slumped soil. This was due the

slightly warmer soil temperatures resulting from the relationship of the

topography to sun exposure. These

sheltered banks received the warmest rays of the sun. Seeing as nobody was

around, for miles, I resorted to crawling and laying around looking in these

ravines for different plants, especially any bryophytes or, even more

interesting to me, any liverworts.

Although I found no liverworts, I noticed that there were some very

small mosses, which were vigorously colonizing forming a continuous green

coating on the freshly exposed peaty soil.

I noticed that these grew only where they had moisture protection from

the wind and very little direct sunlight.

I thought that it was unusual that no other plants grew in association

with these nearly microscopic mosses. Continuing my

exploration I noticed that more than one Jaeger was every so often flying

over me. I lay in wait for one to come

by again but they sought prey now to the south of me. I walked in their direction although they

were quite far away hoping that there might be something interesting inland

and possibly some water. Then I

noticed that a Jaeger was actively hunting reasonably close to me. The Jaeger was hovering and then diving

intermittently. As I was making my way

there I suddenly noticed a dark large bird just sitting on the tundra. The bird seemed unaffected by my

presence. I prepared my cameras and

with my 35mm camera to my eye focused on the bird with greatest stealth

approached the bird as closely as possible as the bird then roused itself by

yawning and stretching one of its wings.

I realized that I had to wait another moment for the bird to become

attentive because the image of a yawning Jaeger seemed highly inappropriate

for such an elegant bird. So just

before it became alarmed took its photograph.

As it took to the air I quickly followed it with my video but I would

have preferred to have taken a highly detailed picture of the Jaeger at close

range in flight. |

|

After a somber evening I

awoke to peer out at the estuary and to take stock of things only to discover

that there was no water out there only mud, lots of mud, everywhere. Somehow in life I have

never learned how to walk on water or to paddle in mud. I suppose that mud paddling might be

feasible but I wasn't in the mood for contemplating this paddling technique

and kedging across mud in a kayak seemed like it would soon transform the

kayak and its paddler into something quite unrecognizable. I decided that I had best content myself

with waiting for the tide. There was a

caribou skeleton just a few feet out in the mud from where I had brought in

my kayak, which I did not find reassuring to look at. After several hours the

water returned sufficiently deep, so I thought, for me to launch in. Unfortunately the water was not quite

enough and it was about as deep as it was going to become. Then came to mind the previous day's

assistance I had gotten from the wind.

It had kindly pushed me into this estuary across these shallows making

paddling here quite easy however my hull had actually hitting bottom more

than I care to remember. Now I

realized that I am confronted with a stiff challenge. The fair weather wind is blowing against me

and my kayak is not floating in this mud.

With greatest effort I am pushing with all my might on my paddle and

scooting myself then I am extracting the paddle for another go at it and my

progress is just a few feet at a time.

The channel is nowhere to be found and actually it is where the mud is

slightly softer than the surrounding mud.

I assume that the channel is further out only to find that I finally

cannot move the kayak at all. Great

patience and fond memories of getting stuck in fresh ice just feet from shore

caused me to just simply back up. I

knew from ice experience that a paddler has more leverage and strength

backing up than going forward. I

backed into the area where I had started from and worked the kayak more

carefully through the softer mud having to retry for the channel several times

when I lost it. It was taking much longer and was more difficult than I had

expected but finally I reached water deep enough. I realized that most of these estuaries are

not deep enough to be explored by kayak except during storm tides. |

|

Once I got to the

outside I was greeted with the same one to two foot seas and fifteen knot

winds continuing from the day before only now because the waves had a little

more time to build up. I made my way

back up the point against a quartering sea on my bow and rounded the point

leaving ample sea room to avoid the wreck there. I decided not to continue farther down the

coast eastward against the wind. I

felt that I had seen enough curious things to feel quite satisfied. Heading around the point

the following sea seemed not too threatening so I stayed a mile off shore

until I had gotten out of its lee, then I discovered that this same sea,

which really didn't seem too threatening on the exposed side of the point was

now a following sea of disconcerting character. Every once in a while a cluster of large

waves would materialize and threaten to throw the boat over on its beam

ends. A few waves managed to slap me

in the face. I was glad that I had as

always stowed and tied down my load not only what little there was on the

deck but below decks as well. I always

pack my kayak with this sort of seas in mind so the seaworthiness of the

kayak does not become compromised, which means that equipment, which must

remain on deck must not hinder the passage of a wave over the decks, be

washed off deck and equipment below deck be packaged in water tight bags and

tied in so as not to brake loose below deck should water enter the

kayak. |

|

028 |

|

I had to adjust my angle

to avoid being blown onto shore in proportion to my speed, which at times

required nearly broadside exposure to the waves. This was one of those moments when I was

glad that I had a "barn door" rudder the traditional Klepper rudder

on my kayak and stout Wenachee paddles with strong, square, wide blades. I have had the experience of paddling a

kayak with an insufficient rudder and very narrow bladed paddles in heavy

wind, which this rudder would have handled.

This was a grim disappointing experience. The kayak, an Arluk III, refused to do

anything but lie broadside until with only the most extreme measures could I

point the kayak down wind. This was

one of those moments, which is best described as "having marginal

control" I felt not just helpless but very foolish. I, like any experienced open water boater

especially a kayaker, feel that one should know what the capability of their

equipment is, work within those limits and not bother having anything but the

best. |

|

|

|

I worked hard to keep my

kayak headed where I wanted having to compensate for the effects of

underwater topography on wave patterns, which to my mind should have been a

following sea not a broadside sea, as I followed the coast westward back to

Barrow. It appears that the southerly

direction of the breaking waves was caused by hydraulic or fluid mechanics

in, which the drag exerted on the edge of the wave by the extensive shallows

gradient would pull the rest of the wave enough to change its direction from

traveling west to traveling southerly.

In a river this effect would result in upstream eddies along the

shores. After a while I

subconsciously synchronized my paddling strokes with the wave pattern so much

so that I relaxed and hummed a tune whose timing matched the wave pattern

perfectly, however I really didn't want to go swimming in this icy water. I arrived back at Barrow

luckily before of the expected migration from the east of ducks. I was concerned about arriving at the beach

should it be lined with a large number of hunters who would be very intent

upon getting their valuable, winter supply of ducks. I was just able to jump out of the kayak

and bring it up on shore before a wave flipped it over or filled it up. On the beach there were

some type of shrimp, possibly krill washing up from great swarms of them

trapped in the cove. There were

beautiful small white with grey and black wings Sabine gulls busily scooping

them up from the surface of the water.

There were no ducks about. Some

sandpipers and phalaropes were working their way along the edges of the waves

gathering shrimp. The shrimp were even

sticking to the hull of my kayak. The

shrimp were very tasty, raw and I could have eaten bowls full of them. |

|

Ice pushed up on Point Barrow while I was on the

east side 029 |

|

I hastily unloaded my

kayak and brought it up onto dry land.

I began carting in my large nylon shoulder carrying bags my gear to a

good tent site in Pigniq near where I had camped before. Mae Ahgeak's children, Marie and Salomi

quickly spotted me and ran over to see me.

I told them how happy I was to see them. This was such a

wonderful moment to be back again. And

sure enough there was Mae again on her three wheeler, offering to help. She figured out how we could manage to load

the kayak and everything else onto her three wheeler and with me balancing

the load and her steering and handling the controls take everything up to my

tent site in one trip. We had fun

knowing that we must have looked like some type of circus balancing act on

our way up the beach and circling around past the cottages. We landed without loosing anything,

especially the 16 feet of kayak I put up my tent and

stretched out my gear everywhere in the bright warm sun to dry because I

wanted to be sure that everything was as dry as possible before I packed it

for the trip home. I found an assortment of

colorful jelly fish among the ice floes beached on the The next few days were

spent visiting exhibits in Barrow, having a wonderful time talking with

visiting scientists and visiting with my friends |

|

Retrieval kayak at Barrow |

|

031 |

|

One warm sunny afternoon

at about When I was waiting to

leave Barrow at the airport it was a deeply touching moment to be bid

good-bye to by an Inupiat lady who was another in the circum polar family of

the Inuit people with just the same person about her as the first lady, Edith

Wilson, who helped me out the moment I arrived at Barrow. As my jet took off I

gazed from my seat out the window down at the mass of ice floes in the |

|

Gail E. Ferris gaileferris@hotmail.com www.nkhorizons.com reedited 3 18 2011 |